The impact of the defeat at Tutrakan (September 1916) on public opinion was very high. The morale of the population and the army diminished so drastically that a major crisis occurred at the level of the army’s superior headquarters, with more tragic consequences than the defeat itself.

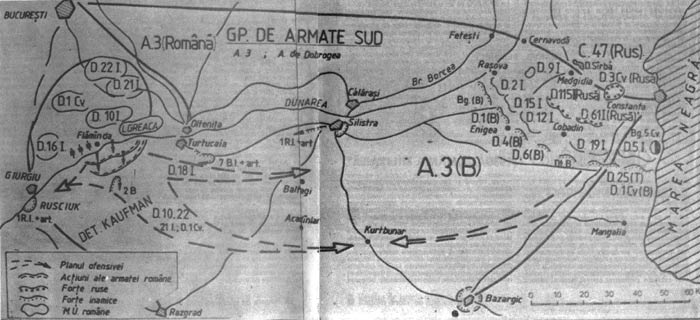

On September 17, General Averescu submitted a battle plan for the approval of King Ferdinand of Romania. The plan to salvage the situation in the south was a modern variant of what the “Moesic diversion” was during the First Dacian War (101-102). The objective was to catch the German- Bulgarian forces off guard while they were on the offensive in the territory between the Danube and the Black Sea through an attack on the Lower Danube. Meanwhile, the Romanian and Russian armed forces (including a Serbian volunteer division), under the command of Russian General Andrei Zaioncikovski, was to start a counterattack on the entire Dobrujean front.

In short, an offensive by a strengthened Dobrujean army, combined with a surprise attack carried out across the Danube, south of Bucharest, launched by a new battle group consisting of five Romanian divisions. The situation was a real “bet against the weather”, as the crossing of the Danube into enemy territory was going to take place in the rainy season.

The crossing of the Danube

The South Army Group led by Averescu became the largest military unit under the command of a single Romanian officer during the Great War. The 128 battalions of the Dobrujean Army and the 58 battalions of the Third Army on the Danube front represented almost half of the Romanian armed forces.

On the other side of the river there was only slight resistance from a small number of troops, enabling Romanian troops in building and enlarging a small bridgehead. In the face of the Romanian offensive only the 217th German infantry division was close enough to react.

Reconnaissance made by German aviation had noticed the mobilization of troops in the south, but General Mackensen erroneously considered that they are being prepared to defend the capital.

On the night of September 30 to October 1, 1916 at three o’clock in the morning, two hundred boats loaded with soldiers from the 5th Vlașca and 20th Teleorman infantry regiments crossed the Danube to the southern shore under the protection of an artillery barrage directed against the Ryahovo, Babovo and Brashlen villages in Bulgaria. By ten o’clock in the morning, the entire 10th Infantry Division was on the Bulgarian bank of the Danube. During the same day, soldiers of the 21st Infantry Division began to cross, while at the same time building a pontoon bridge between the two banks of the Danube. But in the evening, big waves and the bombing by enemy aviation caused a series of difficulties to the construction of the bridge, inflicting casualties among the engineers. Despite these setbacks, at seven o’clock in the evening the works were over. A violent storm followed by a torrential rain the following night broke the bridge in two, but by the next day at six o’clock in the morning, it was repaired.

Taking advantage of the increase in the flow of the Danube from the torrential rains, four Austro-Hungarian vessels penetrate the area of operation. Near the crossing, Austro-Hungarian ships hit the bridge and the Romanian troops that were engaging Bulgarian units on the right bank. Although the bridge did not suffer major damage, the morale of the troops was strongly shaken by the fear of being isolated on the right bank by the enemy. The Romanian artillery returned fire and damaged two monitors, and the enemy ships withdrew.

The operation is suspended

On October 2, Averescu suspended the operation and then headed for the General Headquarters, where withdrawal was decided upon. Despite the general’s desire to keep the bridgehead for the continuation of the offensive on a later date, a total withdrawal was ordered. The decision of the Great General Headquarters came after the defeat at the Battle of Sibiu and after the retreat by the Romanian army in the Olt defile. At the same time, some of the divisions arriving from the Transylvanian Front for the Flămânda offensive are turned back to defensive positions along the Carpathians. Divisions marching from the Carpathians to Dobruja and backwards got stuck on the road and it caused a weakening of the Transylvanian front. At the end of the global conflagration, German general Mackensen said that the Flămânda manoeuvre could have changed the fate of the war in Dobruja.

Selective bibliography:

Glenn E. Torrey, România în Primul Război Mondial [Romania in the First World War], Meteor Publishing House, Bucharest, 2014.

I.G. Duca, Memorii [Memories], vol. I, Expres Publishing House, Bucharest, 1992.

The Count of Saint-Aulaire, Însemnările unui diplomat de altădată: În România: 1916-1920 [The testimonies of a former diplomat: In Romania: 1916-1920], Humanitas Publishing House, Bucharest, 2016.

Florin Constantiniu, O istorie sinceră a poporului român [A sincere history of the Romanian people], Encyclopaedic Universe Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa