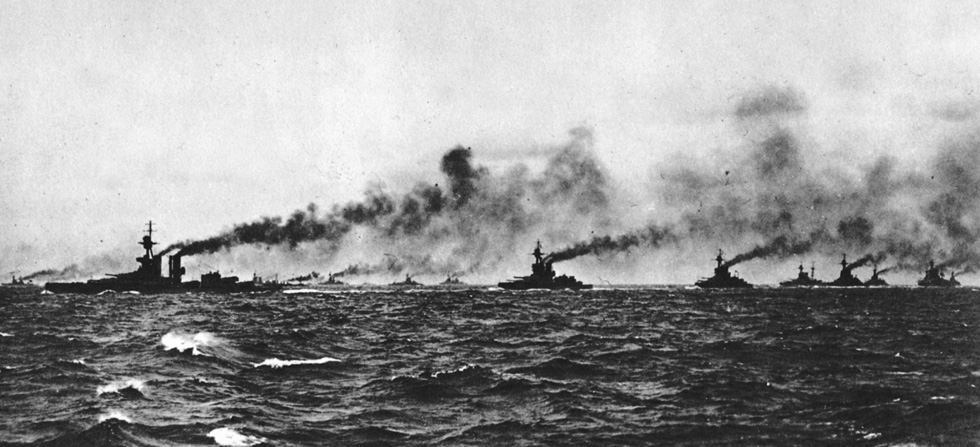

The Battle of Jutland was the largest naval encounter of the First World War, pitting the British Grand Fleet against the German High Seas Fleet. It took place 31 May – 1 June, 1916, about 60 miles off the coast of Jutland (part of Denmark).

In the years prior to war in 1914, Germany had built up a powerful navy to challenge British supremacy. The First World War witnessed a series of naval battles, at Coronel and the Falkland Islands in 1914, and Dogger Bank in 1915. But Jutland was, for both sides, to be the decisive clash.

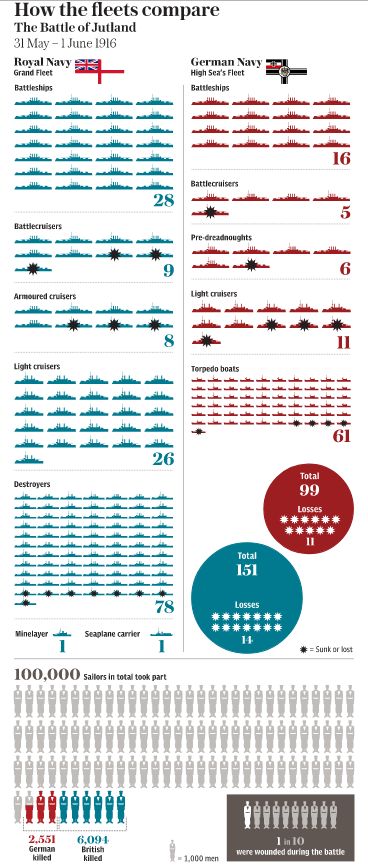

1 Great Britain and Germany possessed the two most powerful fleets in the world at the time

In total, Britain’s Grand Fleet outnumbered Germany’s High Seas Fleet almost 2 to 1. So The battle of Jutland was the biggest naval battle in history up to that point. It was surpassed in scale by the Battle of Leyte Gulf during the Second World War. The Royal Navy outnumbered the German High Seas Fleet since in 1914. At the outbreak of war, Britain had 20 dreadnoughts in service, backed up by 9 battle-cruisers, while Germany had 14 and 4 respectively.

2 German naval strategy during First World War

In 1914 German naval strategy was defensive. German’s naval commanders knew that in a traditional battle like that at Trafalgar the odds would be stacked heavily against the High Seas Fleet. They opted for a strategy of chipping away at the Grand Fleet’s numerical superiority, utilising mines, submarines and raids.

After British Navy install a blockade of Germany, a change of command in 1916 led to a change of strategy for Germany. In 1916 command of the German High Seas Fleet passed from the conservative Admiral von Poul to the aggressive Reinhardt von Scheer. Scheer wanted the High Seas Fleet to pursue a more offensive strategy. In particular, he was determined that the British naval blockade of Germany, by now inflicting heavy damage on her war making capabilities, should be broken for good. Scheer planned to use a smaller force to lure a portion of the Grand Fleet into the path of the High Seas Fleet, where it would be destroyed. Reinhard Scheer wanted the German navy to pursue a more aggressive, offensive strategy. But the British know about this change and planned a trap for German forces.

3 The commanders

The Grand Fleet was under the command of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe

Jellicoe was a highly professional officer with a cautious approach. His deputy in command of the fast battlecruiser force was Admiral David Beatty, a more dashing and charismatic character.

The German force was commanded by Scheer and Vice Admiral Franz Hipper. Hipper was in command of the German battlecruisers, the force sent to lure Beatty into battle.

4 German and British battleship design emphasised different priorities

Battleship design is all about striking a balance between three main factors: speed, firepower and protection. Increasing the strength of one factor must come at the expense of the others if the size of the vessel is to remain within manageable limits.

German dreadnoughts mounted 11″ or 12″ calibre main guns, meaning that on paper they were out-matched by British dreadnoughts fitted with 12″, 13.5″ and 15″ guns. But the German ships were generally better protected, not only by thicker armour plating but also due to being better sub-divided internally, meaning any water taken on due to damage to the hull was better contained.

In essence, British battleships could hit harder but German ships could absorb more punishment and were difficult to sink.

5 The British possessed the most formidable battleships

The Royal Navy’s ‘Queen Elizabeth’ class dreadnought were the first British battleships to dispense with using coal in favour of oil fuel. Its greater thermal efficiency gave them a potential top speed of 25 knots, some 3-4 knots faster than any other existing battleship.

Additionally, they were armed with 8 15″ guns in four twin turrets, using full director gunnery control, which gave them greater firepower than any other battleship afloat.

6 German gunfire was very accurate

Naval gunnery was becoming a science by the start of the 20th Century. The big guns of the dreadnoughts could reach targets as far away as the horizon. To judge range, course and speed, both navies used optical rangefinders.

Germany benefitted from having a superior optics industry. The German Navy used stereoscopic rangefinders that established a correct range fast. British after-battle reports spoke of the superb accuracy of German gunnery, particularly during the first few salvos, often the most vital in a gun action.

7 British gunnery control was superior

The Royal Navy established a system of ‘director firing’ where the big guns were aimed and fired by an officer and a small team mounted in a position high up on a ship’s superstructure where they could see better.

The newest Royal Navy dreadnoughts also had the ‘Dreyer’ fire control system, which produced a continuous ‘plot’ of both ships on a ‘fire control table’. A trigonometrical computer was used to predict where the guns should be aimed next to hit the target.

8 Two British battlecruisers exploded during the battle

HMS Indefatigable and Queen Mary suffered catastrophic explosions after being hit during the opening stages of the battle. HMS Queen Mary was launched in 1912 and commissioned in 1913. She sank at Jutland following a huge explosion, claiming the lives of more than 1200 of her crew.

This was initially attributed to poor armour protection. Modern analysis has also stressed the quality of the cordite explosive used in the ammunition, and the ammunition handling arrangements used in the two navies.

The German Navy had learned valuable lessons at the Battle of the Dogger Bank and had introduced various anti-flash precautions that ensured ammunition fires could be contained rather than spreading to the entire magazine.

9 Both sides claimed victory in the battle

The German Navy claimed more vessels, with the British losing 6 significant ships compared with 2 from the High Seas Fleet.

But it was the British that remained in possession of the battlefield at the end of the action. When Scheer discovered that his plan had backfired and, rather than facing a smaller force of battlecruisers, he was confronted with the entire Grand Fleet, he fled for port.

The battle proved that in no way could Germany’s High Seas Fleet ever hope to win an all-out confrontation with the Royal Navy. After Jutland, Germany’s battle fleet never strayed from port in such strength again.

10 Admiral Jellicoe was heavily criticised

The British public held its navy in high esteem. They expected any naval confrontation to end in the annihilation of the enemy fleet.

When Scheer made his U-turn and headed for port, Admiral Jellicoe took the decision not to pursue him. Had he done so, he may have destroyed the High Seas Fleet and quickened the defeat of Germany.

But Jellicoe was innately cautious. He feared torpedo attack and the loss of further vessels. He was not prepared to risk British supremacy in the North Sea on a dangerous gamble to destroy the German fleet.

His second in command, Admiral Beatty joined the chorus of opposition after the battle, claiming to have disagreed with Jellicoe. By the end of the year, Beatty had succeeded him as commander of the Grand Fleet. Jellicoe was made First Sea Lord.