The second part of 1917 was one of the hardest part of the Great War for the Allied. Russia became an unstable partner on the eastern front. Romania was half occupied, half fighting for surviving but unable to sustain the front if Russia called for peace. In this context Central Powers decided to attack in Italy at Caporetto and to win a bloody victory.

The 1917 Battle of Caporetto was a resounding victory for the Central Powers during World War I. After more than two years of indecisive fighting along the Isonzo River, the Austro-Hungarian command devoted more resources to strengthening the Italian front. Using new infiltration tactics and heavy artillery, the 14th Army overwhelmed its enemy for nearly two weeks, until the Italian line finally held up near the Piave River with help from the French and British. The one-sided battle resulted in some 300,000 casualties and 265,000 prisoners, and contributed to the formation of the Allied Supreme War Council.

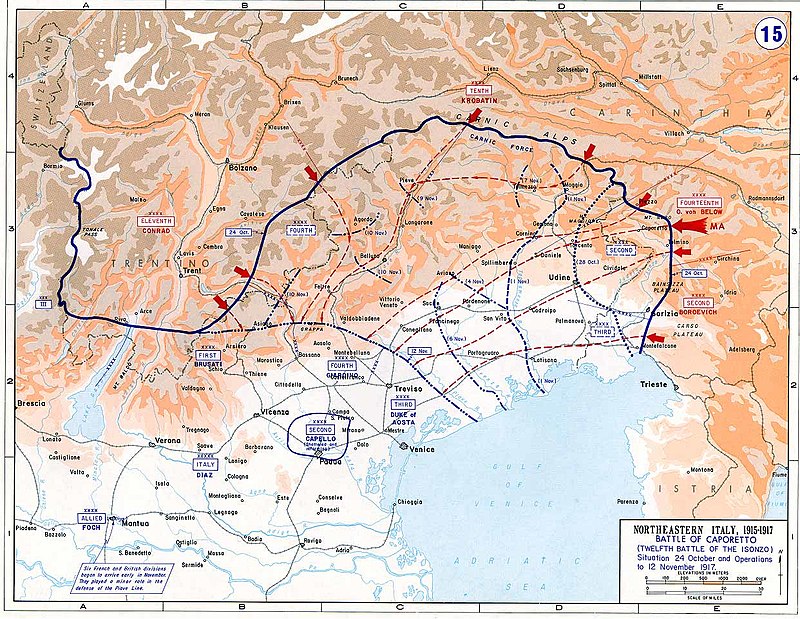

By September 1917, after eleven battles along the Isonzo, the principal theater of war ever since Italy entered World War I, both the Italian and the Austro-Hungarian armies were exhausted. Russia’s collapse, however, enabled the Austro-Hungarian command to strengthen the Italian front and plan offensive operations. Lacking faith in the capability of its allies, the German high command reinforced the plan with seven divisions and heavy artillery, while insisting on operational control. The plan called for an assault along a twenty-mile front on the upper Isonzo, with the village of Caporetto at the center and the Tagliamento River some thirty miles west as the objective.

The attack force, designated as the Fourteenth Army, two German and two Austro-Hungarian corps under General Otto von Below, jumped off on October 24. Using new infiltration tactics, a brief saturation bombardment combining high-explosive and gas shells followed by swift penetration at weak points, the attack routed the surprised Italians. Exploiting success and discarding its initial objective, the offensive continued until November 7, when it reached the Piave (an advance of some seventy-five miles), where the Italians, stiffened by six French and five British divisions rallied. Vividly pictured in Ernest Hemingway’s 1929 novel, A Farewell to Arms, Caporetto was one of the most famous routs in history.

A test of the new German offensive doctrine, Caporetto inflicted 300,000 casualties, including 265,000 prisoners, and temporarily improved Austria-Hungary’s strategic position. The defeat also contributed to the formation of the Allied Supreme War Council. In the end, however, Caporetto could not change the outcome of the war. The scale of their victory has also caught the Germans and Austro-Hungarians by surprise. They were hoping merely to push back the Italians and safeguard Austria-Hungary from further attacks this year, only to realise too late that there was a real prospect of destroying the Italian army and knocking Italy out of the war. As a result their exploitation of the initial victories is not what it might be: Conrad‘s men in the Trentino do not attack with sufficient strength to advance into the Italian rear and the main army’s pursuit runs out of steam as the Italians retreat. Of course the Austro-Hungarians and Germans are advancing beyond their supply lines, making it harder for them to maintain momentum.