The origin of Finns is still a controversial issue among specialists. Generally, archaeologists and linguists agree that a population speaking an ancient Baltic-Finnish language has occupied the southern and western parts of Finland’s current territory since Antiquity. These populations begin to form an independent and original material culture in the second half of the first millennium of our era (550-600).

The invasions of the migratory populations that followed the fall of the Roman Empire did not affect northern Europe, but this situation would change with the Viking period. Beginning in the 8th-9th centuries, the current territory of Finland and its populations became the target of Sweden’s Viking incursions on their way eastward. Until the end of the Viking age (11th century), Finland was not a target for Swedish settlement except the Åland islands. During this time, the Finns were behind their Scandinavian neighbours in terms of political organization. If at the beginning of the second millennium of the Christian era the Scandinavian Peninsula was divided into three kingdoms, the Finns were still organized in tribes.

Finns, between East and West

In the 12th-14th centuries, the Finnish territory became the target of Russian-Swedish rivalry. Following the peace of 1323, the Kingdom of Sweden annexed Finland’s most populous region, the Southwest region. In addition to the political rivalry between the East and the West, the Finns have also been at the centre of religious rivalry. The Russians converted to Orthodox Christianityin the 10th century, but the Swedes converted to Catholicism a century later. Christianity entered in Finland during the 12th century.

The Christianization process took place in Finland differently from the rest of Northern Europe. The Nordic peoples converted to the Christian religion following the Christianization of its leaders, but the Finns have been forced to adopt the new religion by foreign conquerors. Finland has been the target of several Swedish crusades since the mid-twelfth century. Swedish rule was not conducive to the development of a culture in Finnish. Local elites were either of Swedish origin or adopted Swedish language and culture. The Swedish crown was not interested in setting up schools in Finnish, at most only to ensure that the priests were able to convey to the people the Christian teaching in their own language.

Religious reform and the success of Lutheranism have produced important changes in Finnish society since the 16th-17th centuries. Religious books were translated into Finnish, the University of Turku was founded (1640), and Finnish young people were taught to read. At the beginning of the Modern Age, before the introduction of the secular education system, the Church took care of the education of the people and the results of popular education are really impressive. By the end of the 19th century, almost all Finns knew how to write and read. For comparison, in Romania in 1912, over 60% of the population was illiterate.

The birth of the Finnish nation

The foundation of St. Petersburg (1703) brought Finland to the attention of the Russian Empire, the territory under the Swedish rule gaining new strategic and military importance for the Russians. Russia occupied a small part of eastern Finland since the 18thcentury, following military victories at the expense of Sweden, but the annexation of the entire Finnish territory occurred in 1808 in the context of the Napoleonic Wars. Finland became an autonomous Great Duchy, within the Russian Empire.

The concept of Finnish nation formed in the 19th century, under the influence of European romantic philosophy. Finnish nationalism was stimulated by the Swedish and German cultural influences. In the opinion of some historians, the situation of Finland at the intersection of Swedish-Russian interests has led to the emergence of the national movement in this country. Initially, Sweden has not given up hope that it will be able to recover Finland. But the Finns did not want to come back under Swedish rule, nor did they want tobe a part of Russia.

Finnish diplomat and journalist Max Jakobson notes that Finnish intellectuals at the beginning of the 19th century understood that it was necessary to create a distinct identity between Russia and Sweden, for their own self-preservation. The Finnish identity had to be defined, and this had to be done without assuming a political position that could attract Russia’s hostility. The Finnish identity has been asserted throughout the 19th century from a cultural and linguistic point of view.

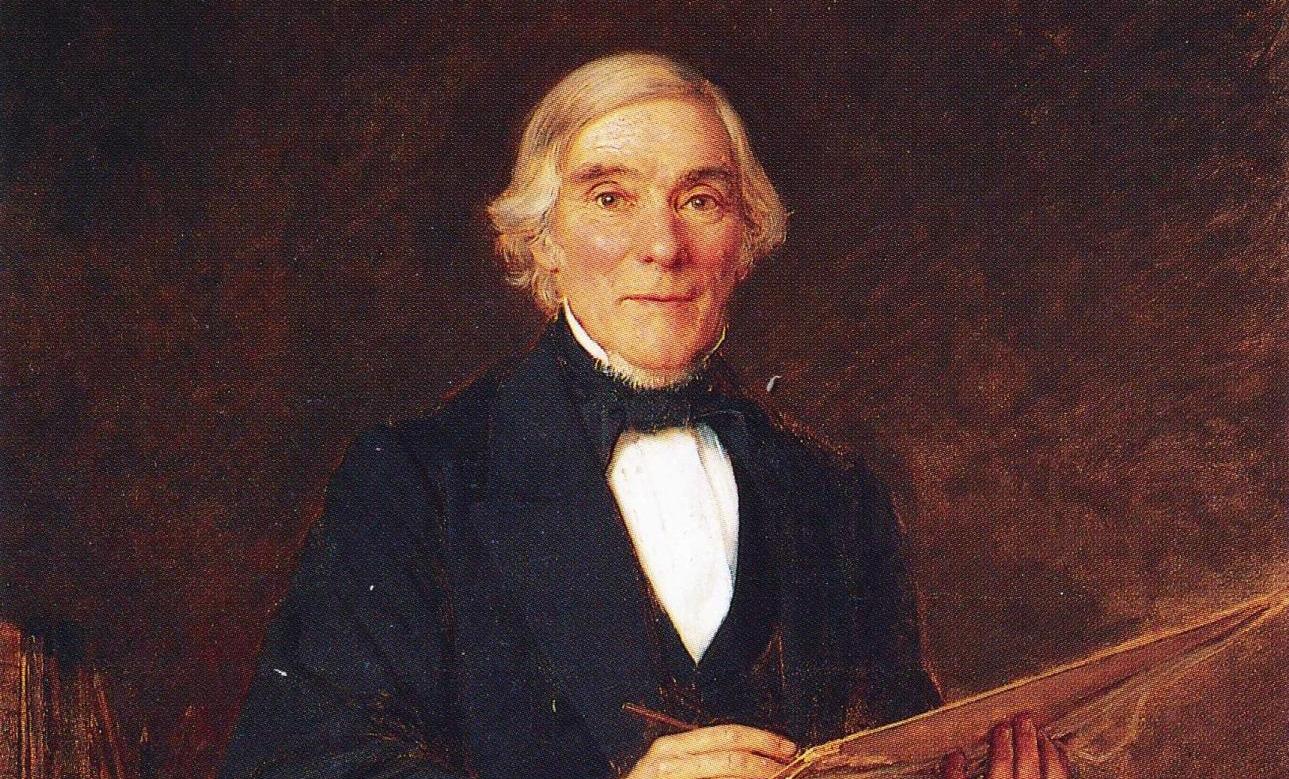

One of the most important figures contributing to the assertion of the Finnish language was Elias Lönnrot (1802-1884). The physician, poet and philologist compiled the vast collection of Finnish folk poems “Kalevala”, originally published in 1835. The “Kalevala” epic was the starting point of Finnish literature and a catalyst for national identity, a Finnish identity that reached its climax in December 1917, when the Finnish Parliament adopted a declaration of independence from Russia.

Bibliography:

Elena Dragomir, Silviu Miloiu, Istoria Finlandei, Cetatea de Scaun Publishing House, Târgoviște, 2010-2011.

Jason Lavery, The History of Finland, Greenwood Pub Group Inc, 2006.