The dismemberment of Austria-Hungary at the end of the First World War offered the oppressed peoples of the Empire a chance to organize themselves in new national states. One by one, the Czechs, the Slovaks, the South Slavs and the Poles forged their own way forward. Even the Austrians and the Hungarians considered it better to organize themselves in national states. So, it was only natural that the Romanians of Transylvania and Banat would also decide that it was time to decide their own future.

Shortly before the end of the war, on October 12, in Oradea, the representatives of the Romanian National Party of Hungary and Transylvania (RNP) approved a document entitled “The Declaration of the Executive Committee of the Romanian National Party of Transylvania and Hungary”, a genuine proclamation of independence centred around the right of self-determination of the Romanian nation “on the basis of the natural law, that each nation alone can order and decide freely of its destiny.”

On October 30, in the backdrop of revolutionary events in Budapest, the Romanian National Council (RNC) is created and became the only political body of the Romanians in Transylvania and Hungary. At the beginning of November, the Council moved to Arad, and on November 6 it addressed a manifesto to the Romanian nation in which it asserted the principle of self-determination and in which the organization of national guards was also formulated. The legitimacy of the RNC was completed by the adherence of the two Romanian Orthodox and Greek Catholic churches, the initiative belonging almost simultaneously to the Orthodox bishop of Caransebes, Miron Cristea (the future patriarch) and to the Greek-Catholic Bishop of Gherla, Iuliu Hossu, future cardinal.

The negotiations

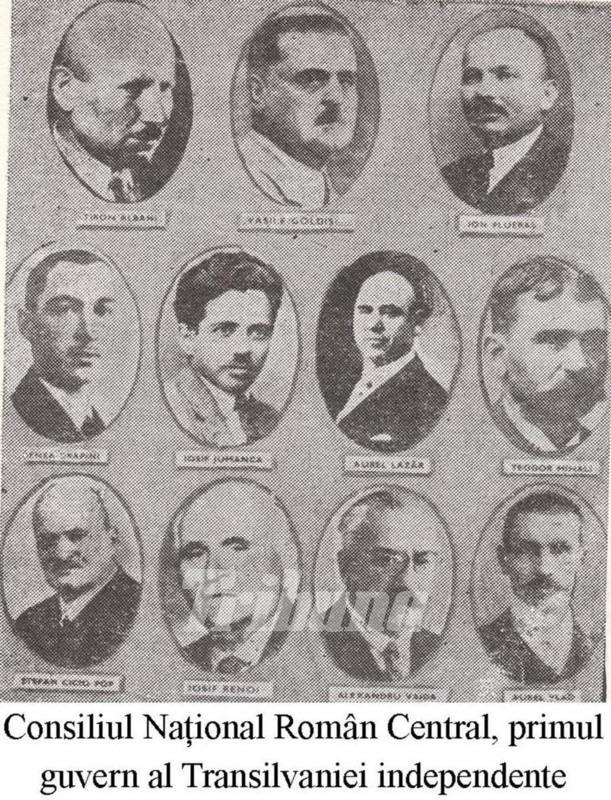

In mid-November, the last negotiations took place between the Romanians in Transylvania and Hungarian representatives, namely between the representatives of the Romanian National Council and the Hungarian National Council. Negotiations started in Arad on November 13 at 10 o’clock. The Hungarian delegation, consisting of 25 people, was headed by Oszkar Jaszi. Both delegations made statements to the representatives of the press, foreshadowing the initial positions of the two councils. The Romanian delegation consisted of Ştefan Cicio Pop (president of the RNC), Vasile Goldiş and Ioan Erdely from the RNP; the socialist representatives were Enea Grapini, loan Flueraş and Iosif Jumanca. Iuliu Maniu would also arrive in Arad.

The start of the negotiations was tense. Vasile Goldiş expressed his disapproval regarding the presence in the Hungarian delegation of the representatives of the National Councils of the Hungarians and Germans from Transylvania on the grounds that the note was addressed exclusively to the HNC, especially criticizing the presence of Istvan Apathy, “the most extreme exponent of the policy of oppression”. It was agreed that “controversial people” should be admitted to negotiations only as observers.

Jaszi specified that he appreciates the Romanian memorandum as correct in virtue of the Wilsonian principle of self-determination. Consequently, he demanded the application of the right of self-determination to other nationalities, citing official statistics according to which 3.9 million other nationalities (Hungarians, Saxons, Székelys and others) lived in Transylvania in addition to the 2.93 million Romanians. He recommended that the Romanian governing body should have a permanent contact with the Hungarian government through delegates, regarding economic, financial, communication and food considerations, considering that the new authorities would not be able to “even provide 48 hours” of food supply.

Regarding the administrative organization, the system that was proposed was one of districts or even smaller, to form the most compact and homogeneous national units, according to the Swiss cantonal model, with their own political bodies gathered then into a larger unit. The proposed project provided for eight smaller enclaves in the Romanian territory and three Romanian enclaves in the Hungarian area. Jaszi recognized the need for a new state order, but called for a provisional form until the Peace Conference met to resolve all controversial issues, including territorial ones.

The Romanian side called for a postponement of the discussions until the next day. The Hungarian delegation was optimistic after the first day. Although it emphasized that the planned solutions were provisional, Jaszi was in fact looking to present the Peace Conference the project of a Hungarian State, where national issues were resolved. His project to create Hungarian, German and Serbian enclaves with an exclusive Hungarian area in the very centre of the territory claimed in Eastern Hungary and Transylvania would have been a major obstacle to the freedom of decision of the Romanians in Transylvania

Neither the subterfuge of exerting pressure on the RNC by including in the delegation the Hungarian and German representatives of Transylvania did not work. On November 14, 1918, the RNC, in the presence of Iuliu Maniu, formulated the answer presented to the Hungarian delegation. The official answer of Vasile Goldiş stated that “The Romanian nation rightly claims full state independence and does not admit that this right will be affected by temporary settlements”. Recognizing the competence of the Peace Congress to set the definitive boundaries of the claimed territories, the RNC assumes “the obligation to respect the Wilsonian principles for the other peoples living on this territory”. Rejecting the suggestions of the Hungarian government, the Romanian side “declines its responsibility for the events that will follow and leaves all responsibility on the shoulders of the Hungarian government. The RNC will preserve public order, the security of wealth and life on the territories inhabited by Romanians”.

“Total separation”

Oszkar Jaszi drew the attention to the fact that the references that alluded to the preservation of public order revealed and demonstrated that the Romanian delegation was in principle seeking the sovereignty of a Romanian national state. He described this option as “very serious” because, in his opinion, only the Peace Conference had the exclusive purpose of resolving state issues. In his speech, Iuliu Maniu stated that “Romanians demand the recognition of their rights based on the fact that they exist as a compact geographic nation with well-defined unitary traditions and aspirations. […] The Romanian nation wants to have its own sovereign state, and the Romanian nation wants to fulfil its national and state sovereignty over the entire territory inhabited by the Romanians of Transylvania and Hungary and cannot admit that obstacles should be put in the way of this sovereignty by way of creating and sustaining foreign enclaves”.

At this stage of the negotiations, Jaszi proposed a new understanding in 11 points, without accepting in principle the demands of the Romanian delegation. On the evening of November 14, Aurel Lazar communicated RNC’s answer to these proposals: “The RNC notes that the negotiations with the minister and the HNC have not reached a principled understanding, that they cannot accept the explanation that they received regarding the right to freely govern, since the Hungarian government does not recognize the right of the Romanian nation to exercise executive power in the territories inhabited by the Romanian nation”.

The negotiations had failed. In a direct discussion between Jaszi and Iuliu Maniu, the first questioned: “What do Romanians want?”, to which Maniu responded “total separation”. The Hungarian society was not prepared for federalist ideas, being incapable of breaking away from the medieval concept of historic Hungary. The Romanians were determined to make their own destiny in a Greater Romania.

Bibliography:

A.J.P. Taylor, Monarhia habsburgică 1809-1918 [The Habsburg Monarchy 1809-1918], Bucharest, ALLFA Publishing House, 2000.

Henri Prost, Destinul României: (1918-1954) [The destiny of Romania: (1918-1954)], Compania Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

The Count of Saint-Aulaire, Însemnările unui diplomat de altădată: În România: 1916-1920 [The testimonies of a former diplomat: In Romania: 1916-1920], Humanitas Publishing House, Bucharest, 2016.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa