Prior to World War I, Poland was a memory, and its territory was divided among the empires of Germany, Russia and Austro-Hungary; these powers along with France and Great Britain were wrestling for dominance of the continent, as illustrated in this serio-comic map. The Germans dominated the resource-rich lands of Silesia and controlled the industrial centers of Posen and Breslau. Germany also controlled the port city of Danzig, known today as Gdansk, which was an important commercial center on the Baltic Sea. Russia exercised jurisdiction over Warsaw and the eastern regions of historic Poland. Austro-Hungary occupied Galicia. The area contained the culturally important city of Lviv (Lemberg) and mines and oil fields found along the Carpathian Mountains. A 1912 Rand McNally map illustrates Europe without Poland.

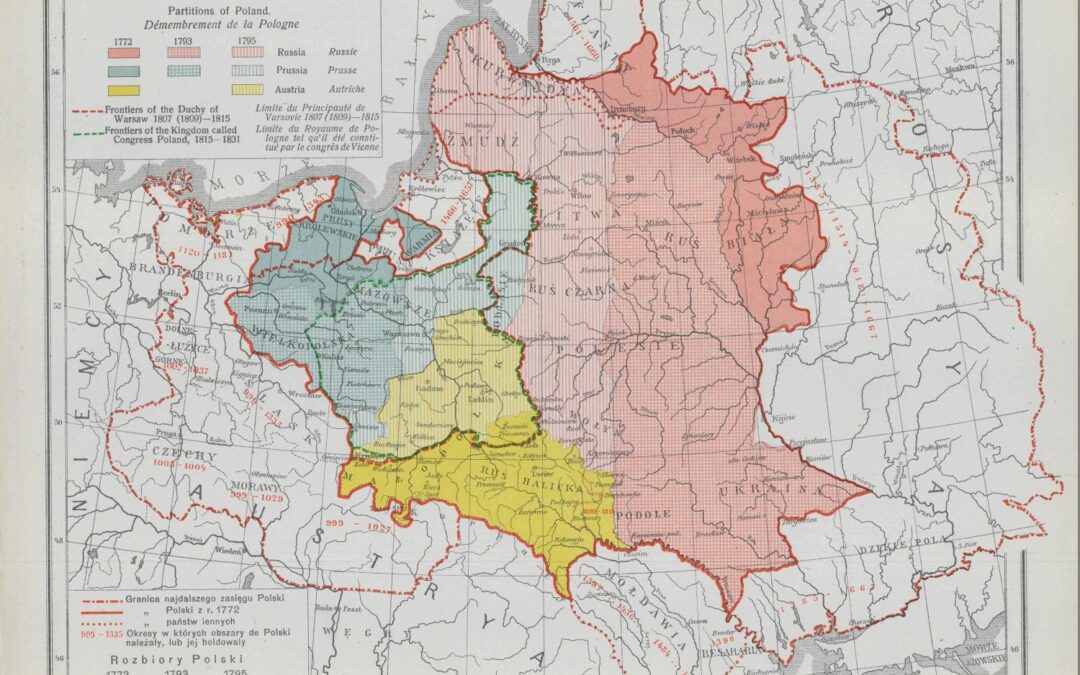

The start of World War I reignited Polish dreams of self-determination. Two years later, in 1916, the Polish cartographer, Eugeniusz Romer (1871-1954), illustrated the rise and fall of his country in this map, pictured left, titled “History.” The map was part of his atlas known as the “Geographical and Statistical Atlas of Poland” that later helped shape Poland’s independence in the Paris peace negotiations of 1919.

Romer produced his atlas in secret, as the authorities of Austro-Hungary, where he lived, reacted harshly to anything that might foment political unrest. Romer combed the archives of the Austrian government, researching census data and economic reports, which he used to craft 32 map plates replete with tables and textual accompaniment in Polish, French and German. His highly detailed depictions included geography, geology, climate, flora, history, political administration, population, ethnography, religious groups, education, land ownership, farming, natural resources and communication networks. The atlas was hailed as a masterpiece.

The Germans and Austrians responded swiftly to stamp out this cartographic declaration of independence, and the publication was banned. Romer was forced into hiding to avoid arrest and prosecution. However, copies of the atlas were smuggled to the United Kingdom and the United States, where it reached policymakers. Upon the American entrance into the war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson articulated the idea of a free Poland among the goals outlined in his Fourteen Points.

The defeat of Germany and Austro-Hungary, and the collapse of imperial Russia, ended the main barriers to Poland’s independence. Poland’s Prime Minister, the celebrated American concert pianist Ignacy Paderewski, along with Romer and other negotiating team members, believed their territory should stretch as far east as Lithuania and should subsume German-held territory in the west and along the Baltic Sea. To the exasperation of the Americans, British and French, the Poles made seemingly conflicting arguments for territory. In the cases of Silesia and the Baltic coast, they argued that the areas had a majority of Polish speakers and therefore should be Polish. Whereas, in the east, in the case of Galicia and modern-day Lithuania, the argued that historic Polish cultural institutions, such as universities and churches, proved that the land should belong to Poland despite Poles being the minority population.

President Wilson and his team were often sympathetic to the Poles; however, Wilson wanted a “scientific” solution and directed his team to draw borders based on the dominant language of the people in a given area, such as in this map found in the Woodrow Wilson papers. Great Britain, on the other hand, was deeply concerned about this approach. They feared Poland would appropriate too much of Germany’s important natural resources and industry in the east. Britain wanted Germany left in a position to pay restitution for the war and to avoid a communist uprising, like the one in Russia.

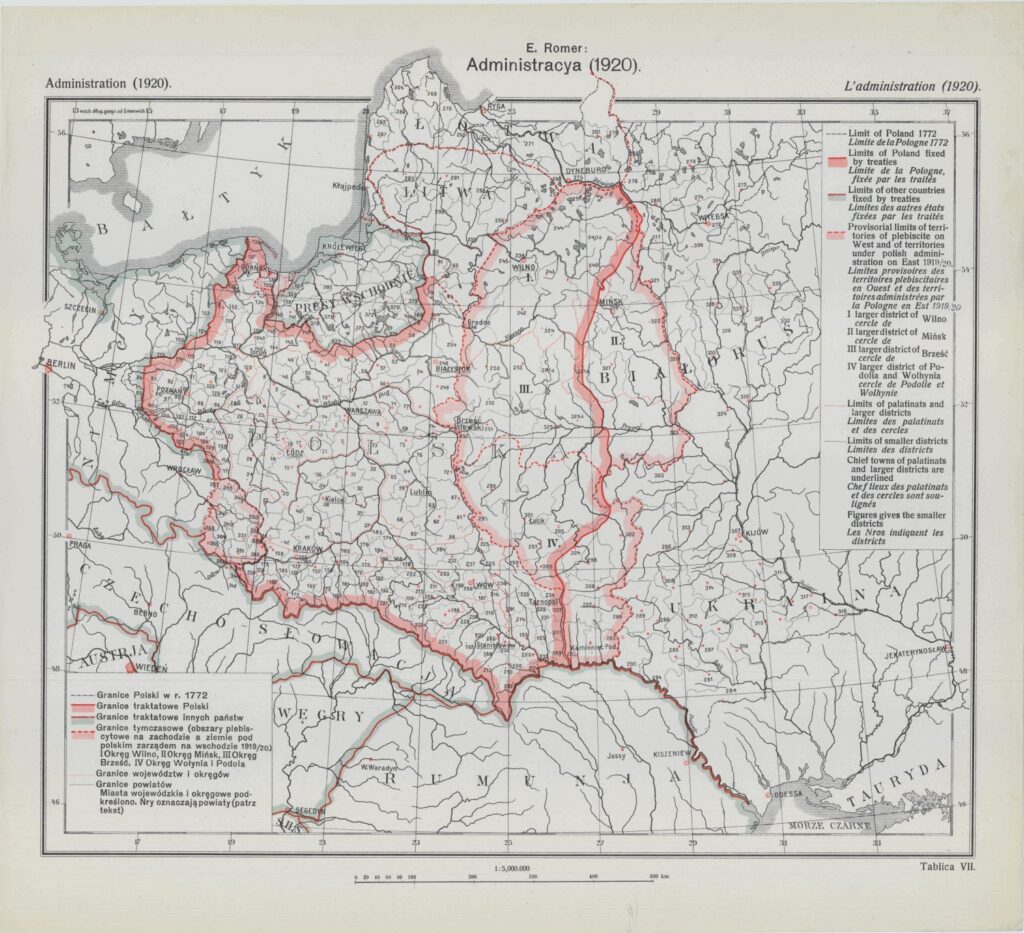

The solution was a compromise that was despised by the Poles and the Germans. The port of Danzig, with its majority German population, was placed under the administration of the League of Nations and placed into a binding customs union with Poland. The port was situated in a narrow strip of Polish territory known as the Polish Corridor. The land was dangerously sandwiched between Germany proper in the west and German East Prussia. Romer illustrated the problem in his map “Administration” (1921), pictured right. Angry about the diplomatic settlement in the west, Poland decided to use military force to achieve its goals in the east. It mobilized an army and appropriated land that included the city of Vilnius and oil fields in eastern Galicia.

In 1919, the Second Polish Republic was born. The country, however, lacked the population and industrial might of its foreboding German and Russian neighbors. It was forced to count on Great Britain and France to provide military assistance. When the hour of need arrived, however, Poland was largely left to fight alone. In 1939, the Nazis overran Poland in weeks, showing the world a new form of warfare called blitzkrieg (“lightning war”). The Nazi’s occupation lasted until 1944 when the Soviet army drove them back into Germany. The Soviets stayed in Poland until 1989. Today, Poland is a free republic and member of the NATO alliance. Its current borders are illustrated in this Central Intelligence Agency map.