The Count of Saint-Aulaire, the French ambassador to Bucharest between 1916 and 1920, was one of the greatest supporters of the Romanian cause both during the First World War and at the Paris Peace Conference. Saint-Aulaire’s memoirs provide lesser known details about the atmosphere during the high-level meetings in Paris in the first half of 1919. The French ambassador, together with Ionel Brătianu, was one of the few politicians who warned of the immense threat that was Bolshevism and of its spread in Europe.

Romania went to the Paris Peace Conference with a clearly defined objective: to make the Allies respect the promises they made in early 1916. The Treaty of Alliance between Romania and the Entente, signed on August 4/17, 1916, stipulated the “recognition by the Entente of Romania’s rights to the territories inhabited by the Romanians in Transylvania, Crişana, Maramureş, Bukovina and Banat, and to be treated similarly in the peace conferences as the other allies”. To these wishes, Romania added the request for the international recognition of the union with Bessarabia.

The intransigence with which Brătianu pursued these goals would soon bring him into conflict with the representatives of the Great Powers and, in particular, with Clemenceau. Here is what Saint-Aulaire had to say about the way in which the negotiations between Romania and the Supreme Council went:

“After this «war of laws», Romania, of all our allies, the one that suffered the most, was the worst treated, on the surface, not in substance. The Supreme Council could not, without denying its essential principle, the principle of nationalities, prevent the country from applying it, and thus achieving its unification and doubling its territory. The obvious justice of its cause and the pressure of European opinion, moved by the immensity of its sacrifices, overcame malignancy.

This war, also called the “war of democracies”, reached an essentially aristocratic peace; elaborated and imposed on the little ones by the «great five», a «Pentarchy» as the Holy Alliance was called which, without raising the banner of democracy, had at least the merit of guaranteeing peace for a longer time. The commitment made to Romania was not taken into account, which, in order to attract it to war, was promised to be on an equal footing with the other allies.

I won the confidence of Brătianu, re-elected President of the Council in December 1918, whose bleak forecasts on the actions of the great five were surpassed. «The foolishness! he said. I would never have believed». He called the Supreme Council the «Supreme Syndicate of Bolshevism». He was astonished by the ignorance and illusions concerning the Russian Revolution, which he compared with those salts that were preserved only in a black bottle and decomposed into light. But the light inspired fear. As for the peace of Versailles, he was not deluded about its duration. He denounced its foremost vice, the contrast between the emptiness of the guarantees and the severity of the conditions, through this picturesque formula: «Wilsonian garlands around Napoleonic clauses». A variant of Jacques Bainville’s appreciation of a treaty «too gentle for what’s hard in it». (…)

«Not even a donkey falls twice in the same marsh»

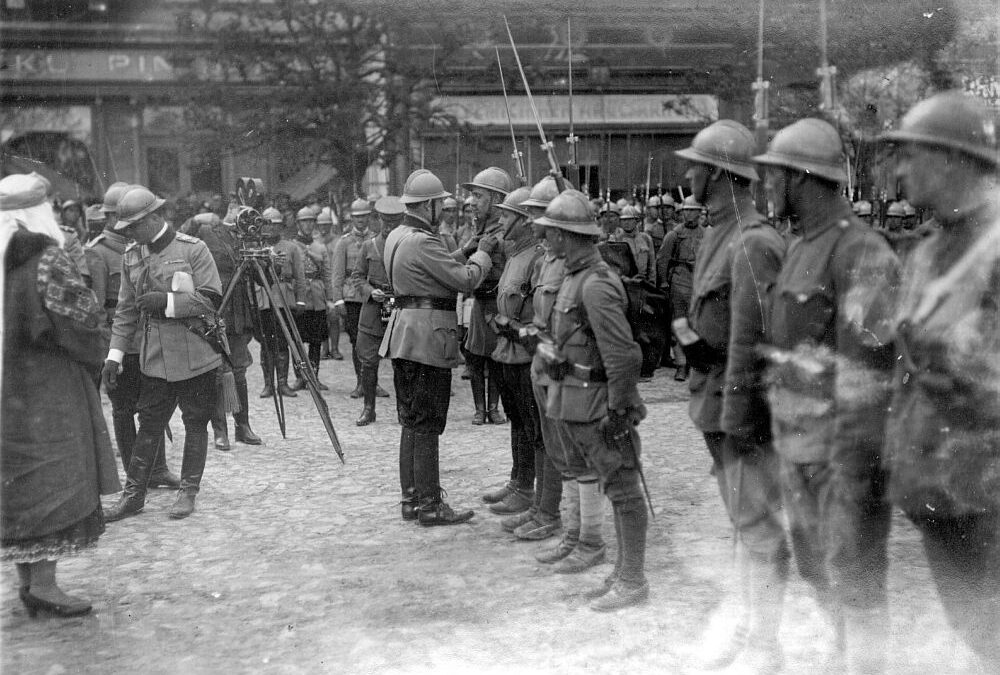

Encouraged by such indulgence, Béla Kun incited atrocities inside and aggression outside. Instead of giving Romania a mandate to destroy his bloody regime on behalf of European interest, the Supreme Council engaged in new negotiations with Béla Kun. He threw an anathema on the Romanians who, without waiting for this mandate, attacked and defeated Béla Kun’s army. And then, after I was about to be recalled because, together with all the Allies, I approved the Romanian-German truce after the betrayal of Russia, I was threatened again with a recall because I supported Romania’s resistance against the Supreme Council’s urging, which wanted to impose an armistice with Béla Kun. Brătianu, who, slamming the door, had just left Paris and the Peace Conference, advised King Ferdinand, as I advised him, not to be intimidated by the Supreme Council’s sluggish threats and, despite its veto, to save Romania and civilization in this part of Europe. On August 3, the Hungarian army was completely destroyed. Béla Kun fled to Vienna. His principal lieutenant and chieftain, Tibor Szamuely, and other revolutionaries, were slaughtered by the population. The Romanian army, under the command of General Moşoiu, occupied Budapest. There he was taken aback by the hostility of the heads of the Italian and English Missions, Colonels Romanelli and Cunningham, as the first sought to make an ally of Hungary against Serbian ambitions in the Adriatic, and the second, following Lloyd George’s instructions, acted insultingly towards Romania, the most faithful ally of France. This twofold scandal had to end: Romania, the only allied country that occupied the capital of its main enemy, and which took from the Bolsheviks a key position that opened all the neighbouring states to its propaganda! Faced with so much recklessness and extravagance, Brătianu quoted the Romanian proverb: « Not even a donkey falls twice in the same marsh ».

The relative ease with which the Romanian army, in spite of this hostility, removed the Russian-Hungarian chancellor, which the great Allies had tried to placate, was another condemnation of their policy of passivity and alternative complicity towards Moscow”.

Bibliography:

The Count of Saint-Aulaire, Însemnările unui diplomat de altădată: În România: 1916-1920 [The testimonies of a former diplomat: In Romania: 1916-1920], Humanitas Publishing House, Bucharest, 2016.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa