In 1918 the United States entered the Russian Civil War on the side of the so-called “Whites,” anti-Bolshevik counterrevolutionaries. This essay explores the decision to intervene at Murmansk and then Archangel, the U.S. Navy’s role in the operations, and the ultimate failure of U.S. policy regarding the young Soviet Union.

How It Began

When a group of radical Russian revolutionaries, the Bolsheviks, seized power in Russia and pulled out of World War I, Russia’s allies, including the Americans, were horrified. They got to work immediately on plans to get Russia back into the war against the Central Powers, especially Germany. The best way to do that, it seemed, would be to send in the navies of Britain, France, and the United States to protect stores of Allied supplies and materiel and, where possible, help the Bolsheviks’ enemies to overthrow the regime and reenter the war against Germany.

The first inkling of a plan to send a U.S. Navy ship to North Russia appears in Navy Department sources for 3 March 1918, when Vice Admiral William S. Sims, the U.S. Navy’s representative in London, forwarded a request to the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral William S. Benson.[3] Would Benson authorize the dispatch of a Navy ship to Russia’s Arctic coast?

The answer was No.[4] The CNO had weightier matters on his mind than the security of Murmansk and Archangel, Russia’s principal Arctic ports. That very day, the Bolsheviks had concluded a separate peace with the Central Powers (the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, 3 March 1918) and handed a stunning victory to the Germans, who might soon be able to divert troops from the war against Russia, now finished, to the war against the western Allies, including the United States. At this point in early 1918, although the United States had been at war with Germany for 11 months, the U.S. Navy was still struggling with a mobilization crisis: how to get American troops to Europe in numbers that could possibly make a difference.[5]

Three weeks later, however, Benson changed his response regarding the Russia situation. In the meantime, the Germans had mounted their first successful offensive on the Western Front since trench warfare had brought on a stalemate in 1914. President Wilson, heretofore reluctant to intervene in the Russian Revolution, now supported limited action by the U.S. Navy to:

“Protect and further” the interests of the Allies “generally” in a defeated Russia vulnerable to further German incursions on its sovereignty.

“Assist in the recovery” of “Allied stores” of materiel at Archangel.

“Use the crews” of Olympia and any subsequent arriving U.S. Navy vessels “to stiffen local resistance against the Germans.”

There was one huge caveat, however: Under no circumstances would U.S. military personnel be allowed to participate “in operations away from the port.”[6]

And yet, come winter, nearly 5,000 American servicemen would find themselves in Russia’s subarctic interior—cold, lost, hungry, and under attack by the Red Army, the Bolsheviks’ increasingly potent and terrifying weapon in what turned out to be the bloodiest conflict in Russia since the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. Ill-equipped, inexperienced, and misguided, American military personnel were trapped in the maelstrom.[7]

USS Olympia to Murmansk

Olympia (Cruiser No. 6) departed from Charleston, South Carolina, on 28 April 1918. Her commanding officer, Captain Bion B. Bierer, was under orders to proceed to the far side of Scotland and then to Murmansk, Russia.[8]

At Kirkwall, in the Orkney Islands, Olympia took on several important passengers. Major General Frederick C. Poole (British Army), the most prominent, took passage to North Russia to assume command of all Allied forces there. Poole’s charge, as Sims understood it, was “to organize the Czech, Serbian and other units” for the effort to keep alive the war in the east against Germany.[9]

In addition to Major General Poole, Olympia also accommodated French naval and military officers as well as a French civilian naval attaché.[10]

They all arrived at Murmansk on the evening of 24 May.[11] Bierer went ashore to meet the local soviet, or legislative and executive council. This soviet had formed as a socialist workers’ institution but now found itself on the wrong side of the Bolsheviks.[12] Many soviets and socialists in Russia objected to the Bolsheviks’ 1917 seizure of power and 1918 exit from the world war, especially as the punishing terms of the peace treaty came to light.[13]

First Landings, June 1918

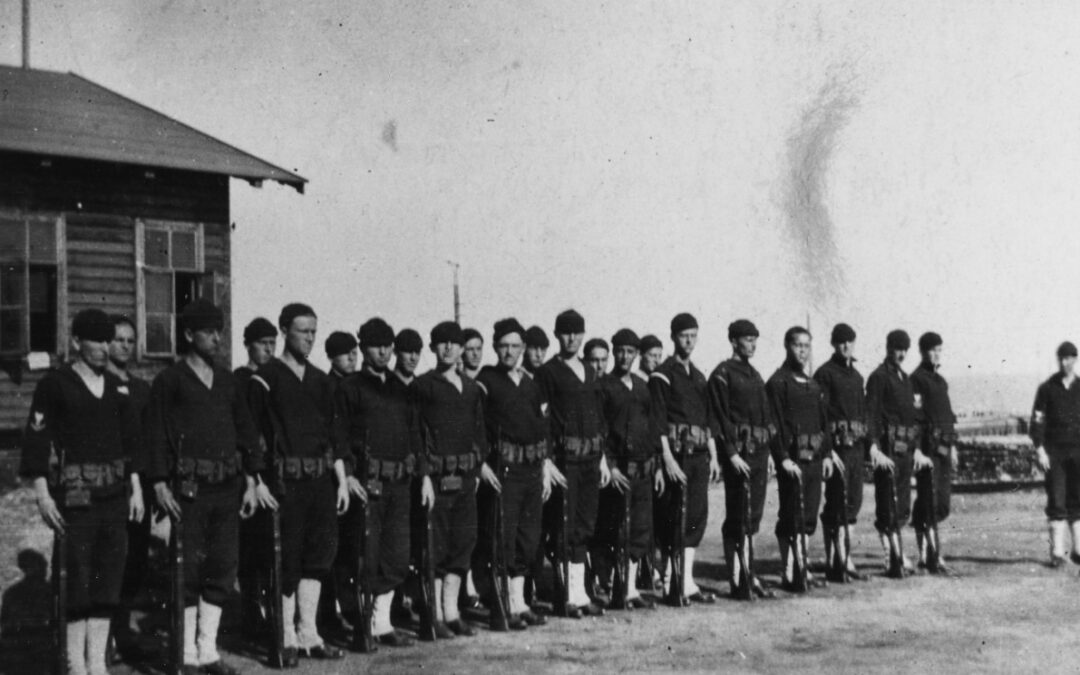

June 1918 saw history’s first landing of a U.S. force on Russia soil. It was small—just 100 enlisted men (Sailors and Marines) and eight officers. Their main mission was to help keep order in Murmansk and, in so doing and by their very presence, assure the populace that the Allies were not about to let the Bolsheviks overrun this crucial northern outpost.

The detachment’s commander, Lieutenant Henry F. Floyd, USN, led everyone to the barracks in town only to find the bunks occupied by the British. With nowhere to sleep, Floyd’s party returned to Olympia.[14] The landing had lasted just three hours and foreshadowed further episodes of poor coordination.

The following day, 9 June, Lieutenant Floyd and his men landed again, this time for the long haul. Not only were they to “assist in preserving order,” fast breaking down in Murmansk, but they were also supposed to “offer such resistance as may be possible to the Germans and the Finns.”[15] The fact that the Germans and their Finnish allies were nowhere near Murmansk did not stop people there from seeing German spies behind every misfortune, accidental or otherwise.[16]

The arrival of hundreds and then thousands of political refugees—most from nearby or from Petrograd or Moscow—contributed to the atmosphere of fear, mistrust, and sometimes panic.[17] Part of the Allies’ mission, therefore, was to relocate these refugees as soon as possible. On 10 June 1918, a complement of Olympia’s carpenters boarded the Portuguese transport ship Porto, under Allied command, to build hundreds of extra bunks. Porto departed five days later, laden with “several thousand refugees,” as well as Petty Officer J. F. Bryant, one of Olympia’s machinist’s mates, to assist.[18]

A Fire, a Riot, a Bombing, and a Mutiny

On 13 June, a British storage facility caught fire and threatened to incinerate the northern end of Murmansk, built as it was almost entirely of wood. The local fire department had no success, and responders were in the process of tearing down surrounding buildings in an effort to halt the spreading blaze when a party arrived from Olympia to put it out.

A large, rowdy mass of onlookers formed around the spectacle. Rumor had it that a German saboteur had started the fire. Arguments broke out—and then fighting. According to Olympia’s war diary, “A [Royal] Marine was accidentally shot through the neck, and a Russian wounded by a bayonet thrust.”[19]

By this point in mid-June 1918, Murmansk was something of a powder keg. Bolshevik sympathizers, a restive minority, had to share this overcrowded outpost with anti-Bolsheviks, many of whom supported the Allied presence and the continuance of the war against Germany. These pro-Allied contingents could be seen egging on the Allied military personnel and diplomats to do even more to counter the Bolshevik threat.[20] Political posters and anonymous broadsides bedecked many walls, fences, and posts all over the former empire, including in port towns like Murmansk. Pamphlets and newspaper reports of dubious veracity circulated from hand to hand and were often read aloud.[21]

Under these charged circumstances, an accidental warehouse fire could easily turn into a riot if the right keywords gained voice: Germans, Allies, Bolsheviks, Americans, War, Peace, and Spies.

There was also the problem of rampant criminality in Murmansk. According to Olympia’s war diary, the crew of a Russian protected cruiser, Askold, had taken to robbing and terrorizing the shore population. The ship’s 200 or so sailors of uncertain allegiance were a “very bad, dangerous lot of men” because of their “habit of going ashore and taking anything they might desire.” Resistance to these robberies, even by local authorities, resulted in the sailors returning later “en masse” and using their guns “in browbeating the people into submission.”[22] With the Allies in charge of policing the town, Askold’s crew almost inevitably came into conflict with Olympia’s shore detachment.

On 12 July, Askold’s crew mutinied. It all began at sunrise, when crewmembers, according to reports, tried to assassinate a Russian naval captain resident in Murmansk. They threw two bombs though his bedroom window, one of which exploded, yet the captain survived unharmed.

Olympia’s shore detail, along with British troops, immediately searched all the houses in the vicinity, confiscated what guns and ammunition they could find, and arrested as many Russian sailors as could be caught.[23] Meanwhile, British troops trained a hail of Lewis gunfire on a rowboat and then two motorboats as their crews, Askold’s mutineers, tried to make the trip from ship to shore. They all turned back.

Eventually, 50 Royal Marines, 50 French marines, and 50 U.S. Marines managed to board Askold, overpower her crew, and gain control of the ship. For good measure, they immobilized the guns by removing all breechblocks and sights. Next, a Royal Navy officer claimed the ship for the king and recommissioned her HMS Glory IV.[24]

On the following day, 13 July, Major General Poole addressed the former Askold’s crew and gave them a choice: They could join the Allied forces in the fight against German aggressors and the Bolsheviks who seemed to abet them, or they could agree to be put on a southbound train, never to return. They chose the latter and likely joined the ranks of the Red Army, in short order.[25]

In the space of a month, there had occurred a possible act of arson against an Allied facility, a riot afterward that resulted in a bullet through the neck of a Royal Marine, an assassination attempt on a key Allied partner, and the defection of a ship’s entire crew to the Bolsheviks—and this in a town, Murmansk, remarkable for its large pro-Allied population.

These events should have given Major General Poole pause. The success of his mission depended on effective partnership with what was left in the region of Russia’s anti-Bolshevik forces. Poole and his Allied troops would soon learn as they pushed deeper and deeper into Russian territory in search of sympathetic locals that the paucity of support for the Allied cause was endemic.[26]

Assisting the Anti-Bolsheviks

Not all mutinies were bad news to the Allies, however. When the Czechoslovak Legion, stuck in Russia but trying to reach the Western Front, refused to take orders from the Bolshevik government and mutinied, gaining control of key stretches of railway, the Allies thought they had found a ready-made army, now fighting for the Allied cause deep within Russia.[27] The Legion’s successes, alongside those of other anti-Bolshevik forces, made intervention seem like a winning course of action.[28]

Unfortunately, the anti-Bolshevik front, a combination of so-called Whites (counter-revolutionary forces, often the elites of the old regime), national separatists (such as Ukrainians and Poles), and other groups (such as the Czechoslovak Legion), on which U.S. State Department officials and their British counterparts pinned so much hope, was in point of fact a ragtag assemblage of loosely coordinated warlords, armies, and gangs, fighting for a variety of irreconcilable reasons and every bit as ferociously merciless as their Bolshevik foes.[29] Wilson’s administration was therefore on the brink of diverting precious U.S. personnel and supplies to a project that could only end in unmitigated disaster: This was a war of all against all in the greatest power vacuum in modern history.

As preparation for this great leap into the Russian Civil War, activity picked up at Murmansk with the arrival of Allied troop transports and still more ships of war. Olympia’s crew observed the comings and goings, detailing everything in the ship’s log and war diary. Particularly remarkable was the arrival of HMS Nairana, a seaplane carrier. Air power would indeed feature prominently in the Russian Civil War, a kind of hybrid, 19th- and 20th-century-style conflict that featured aerial bombardments and cavalry charges alike.[30]

Trouble at Archangel

Unlike Murmansk, Archangel lay under Bolshevik control. Also unlike Murmansk, Archangel was a long-established port city. Although short on food for civilians, the area contained huge stores of Allied supplies, at least a million tons, which the Bolsheviks had been looting in great quantity and sending in the direction of Moscow, to be distributed to Red Army soldiers as they fought their enemies, foreign and domestic.[31] Since Olympia’s arrival at Murmansk, Major General Poole had been grasping for a way to land safely at Archangel, 30 hours from Murmansk by ship, and secure what was left of the stores there.

Poole got his chance on 30 July, when word arrived that there was to be an anti-Bolshevik coup in Archangel the following night. (Poole and British agents in Archangel had helped orchestrate it, in fact.[32]) A “strong force” should set out “immediately” for Archangel to “take advantage of the situation,” as Olympia’s war diary has it.[33]

Once again, Allied leaders chased support wherever and whenever they could find it. They scarce knew that the Archangel expedition and occupation, though successful in the immediate term, would draw them into a protracted and futile war with the Red Army.

Expedition to Archangel, 30 July–2 August 1918

On the night of 30/31 July, three large Allied vessels set out from Murmansk for Archangel: HMS Salvator, with Major General Poole and Olympia’s Captain Bierer embarked; the French cruiser Amiral Aube, with several hundred French troops recently transported to Murmansk on a British steamer aptly named SS Czar; HMS Nairana (the seaplane carrier) with the Royal Navy’s Admiral Kemp on board; and the British steamer SS Stephen with Lieutenant Floyd, commander of Olympia’s Murmansk detachment.[34] Several trawlers accompanied the larger vessels, and four more followed during the day on 31 July. That day also saw the departure for Archangel of a Russian destroyer, restored to service by Olympia’s crew, and four transports. “Practically all vessels carried troops,” according to Olympia’s war diary, “mostly British and French.” Sources vary on levels, but the number of men probably exceeded 1,200.[35]

The first to land were the officers, who had learned at stops along the way that the Bolsheviks did not intend to defend the city. They had already decamped to the other side of the Dvina River and proceeded several miles down the railroad into the woods.

At 8:00 p.m. on 2 August, Bierer’s ship arrived at Archangel’s harbor, the mouth of the Dvina River. Upon seeing the Allies’ arrival, the boats and ships at port blew their whistles, which still could not drown out the cheering of the crowds on the quay. Bierer, Poole, Kemp, and other Allied officers landed by invitation, according to Bierer, and “were received by the representatives of the new White government and a guard of Russian infantry and cavalry.” The occupiers-turned-celebrated-dignitaries then proceeded to a waiting car, which conveyed them to local government headquarters, where Bierer and the others received official thanks for their assistance in ridding Archangel of its Bolshevik masters.[36]

Down the Dvina River

The warm welcome belied a cold reality. In Bakaritza, about 10 miles inland, the Bolsheviks were preparing to fight. The first step would be to draw the Allies into Russia’s interior; the second step would be to keep them there into winter. Only then would the Bolsheviks go on the offensive, having lured their force into a vast, icy trap.

Major General Poole and the others took the bait. Allied troops lost no time in beating a quick trail down the railroad toward the Bolsheviks’ encampment. The Bolsheviks, after a bit of resistance, simply retreated several miles further, past Isagorka.[37]

When some of the Bolsheviks returned to Bakaritza, HMS Attentive, which had come upriver to assist, shelled their positions. HMS Nairana’s airplanes appeared overhead and began to bomb and machine-gun the handful of Bolsheviks below. Twenty-five crewmen and an officer from Olympia took part in the action, finding themselves right in the line of fire.

After only 24 hours of engagement in and around Archangel, the situation for U.S. authorities, military and civilian, was spinning out of control.

By 10 August, the Bolsheviks had drawn Allied troops, including the 25 crewmen from Olympia, farther into Russia. The Olympia crewmen were under the immediate command of Ensign Donald M. Hicks, Lieutenant Floyd having stayed in Archangel proper with the rest of Olympia’s detachment. Hicks and his men accompanied a polyglot Allied force as it boarded barges and small steamers for the journey up the Dvina River. Poole’s orders for them, which sustained subtle changes over the course of August as the War Office in London tried to decide what exactly to do, entailed establishing contact with the Czechoslovak Legion, thought to be nearby; obtaining, with the Legion’s help, if at all possible, “control of the Archangel-Vologda-Ekaterinburg Railway”; finding allies among the local Russian population by recruiting them directly where practicable or otherwise lending support to “any administration”—i.e., local soviets, city councils, or regional warlords—“which may be friendly to the Allies.” Finally, Poole’s men should distribute humanitarian aid and a liberal dose of “judicious propaganda.”[38]

Autumn in the Wilderness

September brought a new commander in chief of Allied forces in North Russia, Brigadier-General Edmund Ironside (British Army), and fresh reinforcements in the form of 4,600 U.S. Army Soldiers.[39] Most of the work for these Soldiers and the Sailors from Olympia consisted in what Ensign James Williamson, USNRF, described as “police and patrol duty.” There was also the occasional trip to Archangel to deliver Bolshevik prisoners of war.[40]

Unfortunately, the men also brought a fresh wave of Spanish influenza, the global scourge of 1918 and 1919. By the middle of September, five U.S. Soldiers had died and another 100 or so were infected and under medical care.[41]

Later in September, when much of the Navy and Marine landing force was able to return to Murmansk and Olympia, it arrived worse for wear, several of the men sick with the Spanish flu and in need of attention from Olympia’s medical officer, himself among the sick but up and working nevertheless.[42]

For the handful of Olympia’s Sailors who remained in North Russia, medicine was increasingly scarce. So was winter apparel.[43] By October, the onset of the North Russian winter, Allied troops found themselves “175 miles past civilization with insufficient food and shelter,” in the words of Sergeant Gordon W. Smith, USA.[44] The Dvina River was frozen, and the port at Archangel would soon be cut off from the world for the next seven months by miles and miles of ice. There was no escape, the land routes back to Archangel often impassable or unsafe.

As night replaced day, the Bolsheviks went on the offensive. “We fought [the Bolsheviks] like cornered animals,” Smith remembers, “many of us bereft of reason.”[45]

Lashing Out in the Dark

The Russian Civil War, it turned out, became more brutal as it progressed, with both Whites and Reds on murderous rampages through wide swaths of Europe and Asia. There developed, in the words of historian Robert Gerwarth, “a never-ending cycle of retaliatory violence.”[46] On the part of the Bolsheviks, recourse to atrocity and terror was the means by which the enemies of the revolution could be liquidated and the gains of the revolution safeguarded and multiplied.[47]

Only in early 1919 did Wilson decide to withdraw American troops from the horrors of North Russia.[48] Most of the American Expeditionary Force (North Russia) made it out in June of that year, having fought and survived in combat a full seven months after the war in the west had ended, on 11 November 1918.[49]

The war in the east, however, would last into 1922 and culminate in the Bolsheviks’ absolute victory. Soviet leaders, including Joseph Stalin, never forgave the Allies for their incursions into North Russian and Siberian territories.

Many factors contributed to the American and Allied misadventure in North Russia, and each offered lessons: about the U.S. approach to the young Soviet Union, about the pitfalls of amalgamation with a foreign navy, about the prosecution of a naval war in several seas at once. The greatest factor, however, was intelligence—that is, the lack of it.

President Wilson had scant information about what was happening on the other side of the Western Front, from the Rhineland all the way to Vladivostok. Part of the problem was a veritable news blackout: German censorship and the Allied blockade of Germany ensured that little information got through about the weakness of the Central Powers. Wilson could not have known, therefore, that the German military was on the brink of collapse even as it mounted its last offensive in spring 1918, nor did he have any way of knowing that the Germans’ ability to control Eastern Europe—and make incursions into Russia proper—was, however ambitious, quite limited in reality.[50] The German army was spread thin, and the state agencies and war corporations there were failing to supply even Berlin, Germany’s capital, with enough food, fuel, and clothing.[51] When U.S. Army troops arrived in Archangel in late September 1918, the German High Command, for its part, knew the war was lost. Allied leaders, however, had no way of knowing that.

Wilson had especially bad information about Russia. Chaos, danger, deprivation, and censorship kept actionable intelligence from Washington. Diplomatic dispatches sometimes never arrived; consular business was disrupted by outright threats to U.S. diplomats, their staffs, and the expatriate communities they served. There was also the lack of clarity about just who represented the Russian state, especially after the Bolsheviks seized power in November 1917. On Russia, there was no intelligence sufficiently reliable or timely for the President to make a decision.

Nevertheless, he did make a decision, which was to intervene, and that decision-making process was marked by misstatements on the part of Ambassador David Francis. An avowed interventionist, he transmitted only the information that supported his cause, even though he witnessed firsthand the resilience and ruthlessness of the Bolsheviks.

Francis was even in a position to put a stop to the use of American troops in North Russia’s interior. Telegrams from Secretary of State Lansing to Francis show that Francis knew no later than 3 August 1918 of Wilson’s intention that U.S. military personnel be used only to guard Allied stores and help police Archangel and Murmansk. No later than 9 August, Francis also knew that British commanders were misusing U.S. personnel. Instead of informing Lansing in a timely manner, Francis politicked the State Department, the Navy Department, and the War Department for more troops, which he had all but promised to Major General Poole for deployment against the Bolsheviks wherever Bolsheviks were to be found.[52]

The most shocking of Francis’s correspondence is a message to Captain Bierer on 31 August 1918, almost a month into the period of misuse of American servicemen. “I hear that American troops will land here not later than Tuesday”—Francis is referring to the Soldiers who would arrive in September—“Hope report is true,” he went on, “and that they will come in sufficient numbers to enable General Poole to advance South to Vologda and south East to Viatka,” deep into Russia’s subarctic interior.[53]

Francis’s memoir, published three years later, tells a more benign story than the diplomatic and military correspondence at the National Archives. These reveal Francis’s behind-the-scenes effort to involve as many Americans as possible in a direct conflict with the Bolsheviks, contrary to the express orders of the President.

Francis’s experience of Bolshevik terror, and his anti-Bolshevism more generally, played a role. Francis, Lansing, and Wilson shared a disdain for communists of all types, at home and abroad. They also appear to have assumed, wrongly, that the Bolsheviks had no mass base and would never win a civil war against the anti-Bolshevik front and the Allies.[54]

Thus, on an assumption that itself was based on a lack of information in some areas and on bad information in others, the Wilson administration sent Olympia, her crew, and then some 4,600 Soldiers into—as one serviceman put it—“that frozen hell.”[55]

—Adam Bisno, Ph.D., NHHC Communication and Outreach Division

NOTE

[1] All Russian dates have been converted to the corresponding dates on the calendar in use in the West.

[2] Thank you to Dr. Susan Corbesero for her advice and help with the finer points of this broadest of narratives. She recommended invaluable secondary sources and shared crucial insights on the dynamics of the Russian Revolution and Civil War.

[3] On Sims’s position and the dynamics of UK/US naval amalgamation, see William T. Johnsen, The Origins of the Grand Alliance: Anglo-American Military Collaboration from the Panay Incident to Pearl Harbor (Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2016), 21–25.

[4] Frank A. Blazich Jr., “United States Navy and World War I, 1914–1922” (Washington, DC: Naval History and Heritage Command, undated), 150.

[5] Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States, 2nd edition (New York: Macmillan, 1994), 354–70. See also the excerpts of a letter from Admiral William S. Sims to Senate investigators on Josephus Daniels’s prosecution of the naval aspects of the recent world war, in Tracy Barrett Kittredge, Naval Lessons of the Great War: A Review of the Senate Naval Investigation, of the Criticisms by Admiral Sims of the Policies and Methods of Josephus Daniels (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1921), 88–91; Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished: How the First World War Failed to End (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), 41.

[6] Vice Adm. William S. Sims, Commander, U.S. Naval Forces Operating in European Waters, to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, cablegram of 15 April 1918; Robert O. Paxton, Europe in the Twentieth Century, 4th edition (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2005), 131.

[7] Sgt. Maj. Ernest Reed, USA, “The Story of the A. E. F. in North Russia,” Current History 32 (April 1930), 66; Edmund Ironside, Archangel, 1918–1919 (London: Constable, 1953), 31; Gerwarth, Vanquished, 41.

[8] Benjamin D. Rhodes, The Anglo-American Winter War with Russia, 1918–1919: A Diplomatic and Military Tragedy (New York: Greenwood, 1988), 4.

[9] Sims to ONI, cablegram of 3 June 1918. In fact, Bolshevik leaders had reached out to the Allies for assistance in fending off possible incursions by the Germans in the west and the Japanese in the east. See Sean McMeekin, The Russian Revolution: A New History (New York: Basic, 2017), 247–48.

[10] Sims to Capt. Bion B. Bierer, letter of 15 May 1918; Folder 9; Box 1268; I-18; Entry 520; Record Group 45; National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC (hereafter: NARA).

[11] Olympia Deck Log, entry of 24 May 1918, Record Group 45, NARA.

[12] War Diary of the USS Olympia from 9 April 1917 to 28 February 1919, entry of 25 May 1918; Navy Department; Office of Naval Intelligence; Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library, 1897–1940; War Diaries, Apr. 1917–Mar. 1927; vol. 354; NARA Washington, DC (hereafter: Olympia War Diary).

[13] Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution, 3rd edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 64–67; V. R. Berghahn, Modern Germany: Society, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century, 2nd edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 55.

[14] Olympia War Diary, 8 June 1918.

[15] Ibid., 9 June 1918.

[16] Christopher Dobson and John Miller, The Day They Almost Bombed Moscow: The Allied War in Russia, 1918–1920 (New York: Atheneum, 1986), 43.

[17] Ibid., 58–60. On the refugee crisis more generally, see Gerwarth, Vanquished, 93–95.

[18] Olympia War Diary, 10 June 1918 and 15 June 1918.

[19] Ibid., 13 June 1918.

[20] Dobson and Miller, Day They Almost Bombed Moscow, 60; Ironside, Archangel, 176.

[21] On rumors, see Donald J. Raleigh, Experiencing Russia’s Civil War: Politics, Society, and Revolutionary Culture in Saratov, 1917–1922 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 64.

[22] Olympia War Diary, 12 July 1918.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Dobson and Miller, Day They Almost Bombed Moscow, 57–58. The Czechoslovak Legion was trying to go east in order to go west. Their plan was to fight their way down the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok, where ocean-going transports would take them the long way around to Western Europe. This eventuality prompted Wilson to authorize intervention in Vladivostok as well as in North Russia. –“Allied Intervention in Siberia and Russia,” State Department report, forwarded to the Chief of Naval Operations by Rear Adm. Roger Welles, Director, Office of Naval Intelligence, 11 July 1918; Folder 10; Box 706; Entry 520; Record Group 45; NARA.

[25] Dobson and Miller, Day They Almost Bombed Moscow, 58.

[26] In fact, “Entente troops were already involved in skirmishes with the Reds in the North,” according to Liudmila Novikova, An Anti-Bolshevik Alternative: The White Movement and the Civil War in the Russian North, trans. Seth Bernstein (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2018), 56: In the “context of the Allies’ broader efforts in World War I,” she shows, “operations in the area began as an alliance with the local soviet against German-Finnish forces.” Only later did these operations “inadvertently” turn “into an anti-Bolshevik campaign.” Cf. McMeekin, Russian Revolution, 282.

[27] Fitzpatrick, Russian Revolution, 74; Paxton, Europe, 32; Gerwarth, Vanquished, 83–85.

[28] “Allied Intervention in Siberia and Russia,” State Department report, forwarded to the Chief of Naval Operations by Rear Admiral Roger Welles, Director, Office of Naval Intelligence, 11 July 1918; Folder 10; Box 706; Entry 520; Record Group 45; NARA. See also Jonathan D. Smele, Civil War in Siberia: The Anti-Bolshevik Government of Admiral Kolchak, 1918–1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 215. Paxton, Europe, 32; McMeekin, Russian Revolution, 264. Around this time, summer 1918, the United States actually received requests to intervene from the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly, or “Komuch,” an anti-Bolshevik force. –Gerwarth, Vanquished, 84.

[29] David R. Stone, “The Russian Civil War, 1917–1921,” in The Military History of the Soviet Union, edited by Robin Higham and Frederick W. Kagan (New York: Plagrave, 2002), 13.

[30] Olympia War Diary, entries of 11–26 July 1918. On defining, delineating, and periodizing this war, see Jonathan D. Smele, The “Russian” Civil Wars, 1916–1926: Ten Years that Shook the World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 8–17ff.

[31] Jamie Bisher, White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian (New York: Routledge, 2006), 32; Dobson and Miller, Day They Almost Bombed Moscow, 61.

[32] Clifford Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade: The British Invasion of Russia, 1918–1920 (London: Bloomsbury, 2006), 29ff. On conditions at Archangel and an account of the political intrigues from Russian perspectives, see Novikova, Anti-Bolshevik Alternative, 46–65.

[33] Olympia War Diary, 30 July 1918.

[34] Ibid., 31 July 1918.

[35] Bierer, report in Olympia War Diary, 2 August 1918.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Rhodes, Anglo-American Winter War, 42.

[39] One Regiment Infantry (339th, 3,650 men), one Battalion Engineers (750 men), and one Sanitary Train (200 men), according to a report by Lt. Henry F. Floyd in Olympia War Diary, 8 September 1918.

[40] Ensign James C. Williamson, report in Olympia War Diary, 7 September 1918.

[41] Ensign John M. Griffin, letter quoted in Olympia War Diary, 19 September 1918.

[42] Olympia War Diary, 20 September 1918.

[43] Commander P. H. Edwards, Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, letter quoted in Olympia War Diary, 19 September 1918.

[44] Sergeant Gordon W. Smith, USA, “Waging War in ‘Frozen Hell’: A Record of Personal Experiences,” Current History 32 (April 1930), 69.

[45] Ibid. Cf. Reed, “Story of the A. E. F.,” 66–69, who describes the collapse in morale and a string of mutinies.

[46] Gerwarth, Vanquished, 88.

[47] Bolsheviks were direct and forthright about the “Red Terror” in their public incitements to violence against the Revolution’s enemies, perceived and real. The “White Terror,” on the other hand, was directionless and random, except in the case of Jews, who were consistently victimized by the Whites’ rabid and vicious anti-Semitism. See Fitzpatrick, Russian Revolution, 76–77; Gerwarth, Vanquished, 81, 88–91, and 96.

[48] Rhodes, Anglo-American Winter War, 100.

[49] Ibid., 106–109.

[50] Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius, War Land on the Eastern Front: Culture, National Identity, and German Occupation in World War I (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 89ff; McMeekin, Russian Revolution, 264.

[51] See Belinda Davis, Home Fires Burning: Food, Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000), especially 76–92 and 159–89.

[52] Olympia War Diary, 31 July 1918; Rhodes, Anglo-American Winter War, 42. Francis, in his memoir, seems to place himself at Archangel before 9 August, but Olympia’s War Diary has him on board at Murmansk from 31 July: David R. Francis, Russia from the American Embassy, April, 1916–November, 1918 (New York: Scribner’s, 1921), 266–69.

[53] Francis to Bierer, letter of 31 August 1918; Folder 9; Box 1268; I-18; Entry 520; Record Group 45; NARA.

[54] Paxton, Europe, 132. On Wilson’s profound misunderstanding of Russian, East European, Southeast, and Central European affairs, particularly with respect to nationalism, Bolshevism, and the Whites, see McMeekin, Russian Revolution, 285; Joan Hoff, A Faustian Foreign Policy from Woodrow Wilson to George W. Bush: Dreams of Perfectibility (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 39–49; Robert J. Maddox, The Unknown War with Russia: Wilson’s Siberian Intervention (San Rafael, CA: Presidio, 1977), 138; Andreas Rödder, Wer hat Angst vor Deutschland? Geschichte eines europäischen Problems (Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 2018), 84; Gerwarth, Vanquished, 99. Cf. Rhodes, Anglo-American Winter War, x and 99.

[55] Smith, “Waging War,” 70.