By defeating the Red Guards and taking control of the Siberian railway, the Czechoslovak Legion gave a helping hand to the White movement, a loose coalition of forces opposed to the new Bolshevik regime. Moreover, the Whites even requested their help, hoping for a while that Russia’s fate will follow a different path.

In June 1918, the Czechoslovak Legion was in Penza, a town near Samara, the capital of the Volga region, where the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR) leaders were in hiding. They contacted the Czechs, asking for their help in the overthrow of the Soviets from Samara. The demand contradicted the general policy of the right SR who claimed that foreign troops should not be involved in the struggle of the people against the Bolsheviks. But the leaders of the party managed to convince the right SR that the intervention was justified. The Czechoslovaks, who in turn had decided not to engage in the civil war in Russia, wanted to continue the fight against the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but that depended on the removal of the Bolsheviks from power. Moreover, the Allies were also involved- seeing how easy the legion defeated the Soviets in Siberia, they were in agreement that the Czechoslovak struggle was paying off.

One of the arguments the SR used to persuade the Czechoslovaks to fight with them were their alleged ties to the French government- ties that would ultimately prove to be almost non-existent. Believing this, the troops of the Czechoslovak Legion finally agreed to help the SR in the fight against the Bolsheviks and in the conquest of Samara.

The conquest of Samara

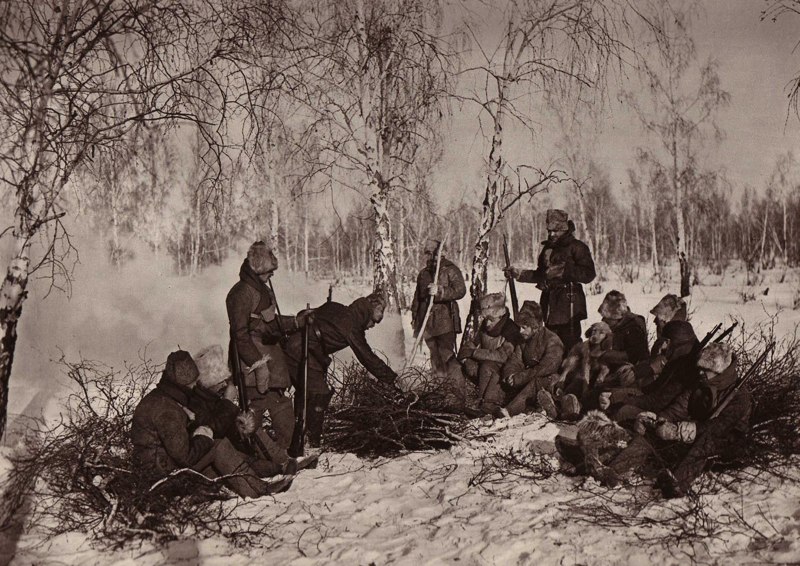

The city on the Volga was in a state of chaos following countless strikes and a recent riot by the garrison. From a population of 200.000, the Soviets could not convince more than 2.000 men to join the Red Guards, most of whom were Latvian laborers evacuated during the war. It seemed that the Bolshevik chances were significantly against them as they faced the 8.000 well-armed Czechs, especially since many of them simply fled at the sight of the Czechoslovak Legion. Nonetheless, there were some who stood and fought and, in the ensuing battle, 6 Czechs and 30 members of the Red Guards died.

When the conquest of Samara was finished, it became the seat of the Constituent Assembly or Komuch, which fashioned itself as the Russian National Parliament in exile. The five founding members were all members of the SR, three of whom were from Samara. Still believing that if they continue fighting the Bolsheviks they will eventually fight against the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Czechs stood side by side with the Constituent Assembly and during the summer they managed to effortlessly conquer other Bolshevik controlled cities.

However, without a standing army, the Constituent Assembly was beginning to lose ground quickly in front of the Bolsheviks who were organizing themselves better day by day. At the end of the summer, the Czechs no longer wanted to fight. The soldiers were tired and wanted to continue their journey to Europe, to their homes. Some of them even changed sides, falling prey to Bolshevik propaganda while others had altogether given up, selling their supplies to the locals.

The news of the Czechoslovak Legion’s deeds in Siberia reached the United Kingdom, France and the United States. In July 1918, US President Woodrow Wilson yielded to Allied pressures and sent help. US and Japanese troops went to Russia to rescue the Czechoslovak Legion, which was blocked by the Bolsheviks in the Transbaikal region. Even so, before the “saviours” could arrive, the Czechs broke through and had already reached Vladivostok. In autumn 1918, 70.000 Japanese, 5002 Americans, 1400 Italians, 829 British and 107 Frenchmen arrived in Siberia, and they continued the fight against the Red Guards.

Through their struggle against the Bolsheviks in the spring and summer of 1918, the Czechoslovak Legion garnered the support of the Allies which then backed the cause of Czechoslovak independence.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa