The beginning of the First World War represented for the Czechs and Slovaks a major opportunity to fight for their independence against the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Representatives of these minorities in Russia proposed to that country’s government to support their struggle and in return they would fight for the cause of the Entente, side by side with the Russian army. The Russians agreed, and on August 5, 1914, everything became official, the STAVKA- the Grand Headquarters of the Russian Imperial Army- agreeing to set up a battalion of Czech and Serbian volunteers.

The new legion, or Druzina, as the Russians called it, left to join the Russian Third Army in October 1914. There, the Czechs were divided into several units, with various duties like reconnaissance, prisoner interrogation, or subversion of enemy troops.

After a few months, the Czechs and Slovaks wanted more: to turn the battalion into a true combat unit. For this, however, the only solution was to recruit Czech and Slovak prisoners from Russian camps. The Russians agreed at the end of 1914 only for them to change their minds a few weeks later. Following unwavering insistence and pressure on the Russian government, the Czechs only succeeded in being outright forbidden to recruit their fellow countrymen from the prisoners the Russians had captured from the Austro-Hungarian army. However, the Czechs did not give up and managed, on a much smaller scale, to bypass this prohibition by making arrangements at a local level with Russian military authorities. Even so, between 1914 and 1916, the Czech legion in Russia grew very little, but distinguished itself during Kerensky’s offensive in July 1917, when they succeeded in winning in front of the Austro-Hungarian army in the Battle of Zborov.

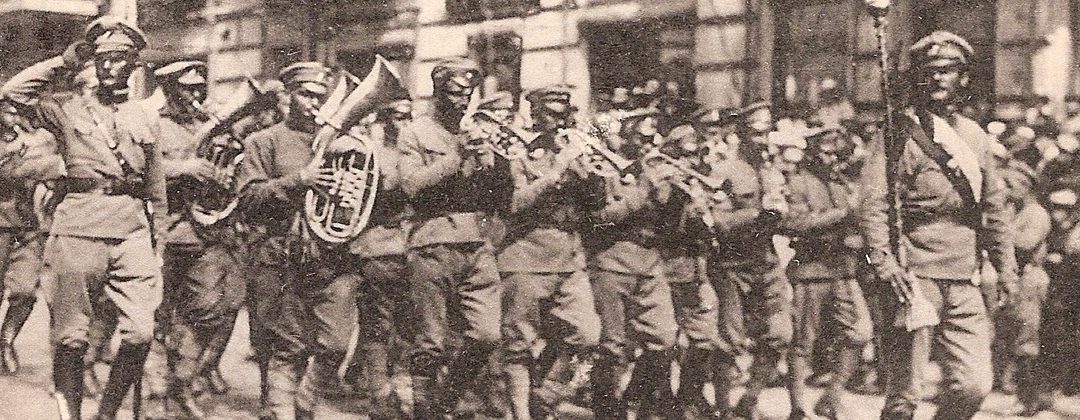

It was only after this victory that the Provisional Government concluded an agreement with the Czechoslovak National Council, allowing them to recruit from among the prisoners of war. In the summer of 1917, the First Czechoslovak Division, which consisted of four regiments, was created- and so, the Czechoslovak Legion was born. A second division, made up of another four regiments, was added, the Legion numbering over 40.000 soldiers at the beginning of 1918.

The game of mistrust

Russia’s internal policy, however, threw the plans of the Czechs in disarray. With the arrival of the Bolsheviks in power in November 1917 and the start of peace talks with the Central Powers in Brest-Litovsk, the Czechoslovaks- through Tomas Masaryk, the National Council leader- decided it was time to leave Russia and continue its struggle against the Central Powers in Western Europe, more precisely in France. At that time most ports were blocked, with the only one that was readily available being Vladivostok. Initially, the Bolsheviks agreed, allowing them to head to Vladivostok- a 10.000-kilometer trek. Their journey from Ukraine to Soviet Russia was interrupted by the Germans, who tried to stop them at the Battle of Bakhmach, in the beginning of March 1918.

Representatives of the Czechoslovak National Council resumed negotiations with the authorities in Moscow and in the Penza Oblast to conclude the terms of the Legion’s withdrawal from Russian territory. On March 25 they came to some understanding, based on mutual mistrust: the Czechoslovaks had to surrender all arms and ammunition in return for safe passage to Vladivostok. Even if the Czechoslovaks decided to adopt a neutral attitude towards Russia’s new government, the Bolsheviks did not believe them. Moreover, they suspected that they wanted to join the counterrevolutionaries. On the other hand, the Czechoslovaks were worried about the pressure put on the Russians by the Central Powers to ban their departure.

The evacuation of the Czechoslovak troops turned out to be much more difficult than expected. The biggest problem was, of course, the local authorities with which they had to contend with along the way. On May 14, at Celebinsky, a conflict broke out: the legion heading east met with Hungarian prisoners of war going westward that were being repatriated. Then, war commissar Leon Trotsky ordered the disarmament and the arrest of the legion’s members. After several days of negotiations, the Czechoslovaks refused the Russian request, and this incident triggered the Revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion.

“In Russia, there were many difficulties, most of them with the Russian authorities, who could not understand our cause: they considered us Austrians and traitors of out Emperor- they betrayed the Emperor, they will betray the Tsar. We wanted to be allowed to form an army to fight against the Germans from our prisoners of war, and after allowing us in creating some regiments, we wanted to create our own army corps. God, I’m not surprised that the idea was not to their liking. They were afraid that if they allowed us this thing, they would be forced to allow the Poles to do the same, and they did not trust them. Not only that but they did not have enough clothes or weapons for their own soldiers, and now they had to arm ours as well. Many Russians were against it, as they needed our prisoners as skilled workers in factories, in mines, working on railways and in the fields”, Tomas Masaryk would later recount.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa