In August 1918, the German army was about to be defeated on the western front. In just over a month, with the advance of the French army in Thessaloniki, the Bulgarian front collapsed. On September 26, the government of Sofia called for an armistice (signed in Thessaloniki on September 29). A few days later, the Ottoman Empire realizing the hopelessness of the situation, called for an armistice on October 14-15 (signed at Mudros on October 30). Under these circumstances, the Habsburgs sought to obtain peace under any conditions or terms: recognition of the dynasty was the only thing that mattered. On October 4, Austria-Hungary accepted Wilson’s 14 points, leaving to him the task to decide the fate of the Monarchy. But as the Austro-Hungarian disintegration process could not be stopped, every nation wanted to decide its own future.

On October 21, the Czechoslovak government in Paris issued an official declaration of independence. On October 28, the Czechoslovak Republic was proclaimed in Prague. Slovaks recognized the new state on October 29. The Slovenians and Croats, deprived of the protection of the Habsburgs and defenceless against the Italian dangers, chose the lesser of the two evils and accepted the union with the Serbs. The Yugoslav state was proclaimed in Zagreb on 29 October, and an improvised National Council took power the next day. The Habsburg dynasty lost not only the support of its subject people, but the sovereign nations had in turn lost any interest in it, once the idea of their supremacy over the “inferior races” had shattered.

Hungarians and Greater Hungary

The Hungarians were still determined to keep Greater Hungary. Separation meant, in principle, the maintenance and defence of the Habsburg crown, which was a symbol for the unity of the lands of the Hungarian “holy crown”. But once the Habsburgs had disappeared, or, worse, recognised the new national states, the only remaining alternative was the path opened by Kossuth, in 1849, the revolutionary republic. On October 31, Mihaly Karolyi was appointed Prime Minister by Emperor Charles by telephone. Three days later he could announce that Kossuth’s dream had come true, with the approval of the Habsburgs. But the conviction that Hungary would be a union of people of equal status will prove to be nothing less but pure utopia. On October 16, 1918, the Hungarian government announced to Parliament that, due to the federal reconstruction of Austria, it revokes Law XII of 1867, but maintains the Pragmatic Sanction. Based on this, only a Personal Union is maintained between the Austrian Federal State and the “lands of the Hungarian crown”. There also was a promise to revise the Hungarian-Croat Compromise (Law XXX of 1868), which was considered essential for Hungarian nationality policy. The debates that followed in the Hungarian Parliament marked the political rise of the opponents of the alliance with Germany and supporters of the Ententes, grouped around Karolyi in the Independence Party, as well as the left-wing parties, whose position on the issue of nationalities and the Personal Union with Austria did not coincide with those of the government. Tributary to a sense of belonging to the nobility of feudal origin Karolyi remained an adept of the territorial integrity of historical Hungary and the superiority of the Hungarian nation over the other nationalities, especially over Romanians.

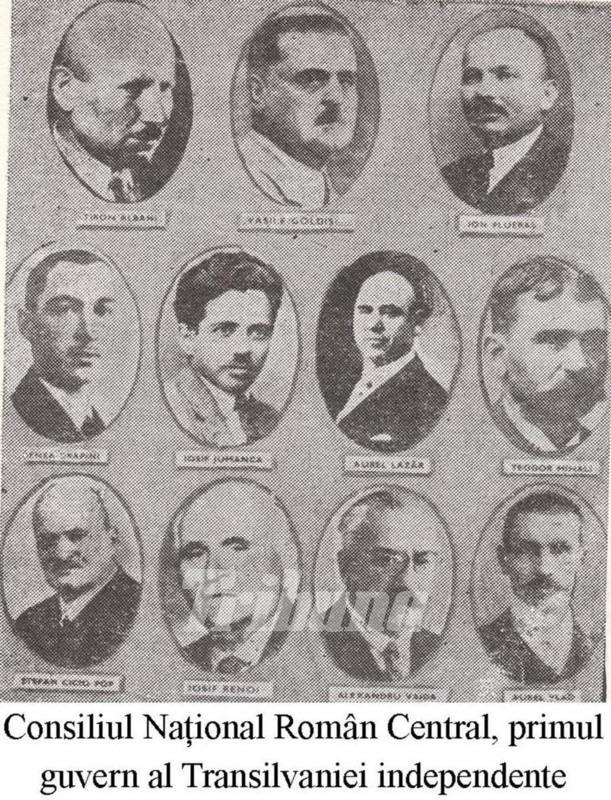

On October 25, the Hungarian National Council (HNC) was formed, consisting of representatives of the Independence Party, the Radical Party and the Social Democratic Party. The next day its program was made known by a proclamation; it was composed of 12 points. Among other things, it proclaimed the establishment of a democratic government (without specifying the form of government). A distinct point stipulated the preservation of the integrity of the Hungarian state through a “brotherly alliance of equal peoples…based on common economic and geographical interests and not on national adversity”. The HMC recognized the existence of the Ukrainian, Polish, Yugoslav and Austrian states, while for Romanians and Slovaks only cultural autonomy, communal and urban self-government was accepted, but not territorial autonomy. Romanians from Transylvania, Banat and Maramureş created a Romanian National Council on October 30, and then organized the Great National Assembly at Alba Iulia, which decided to unite these provinces with their motherland- the Kingdom of Romania.

The Habsburgs remain alone

In turn, the German Austrians followed the example of the other nations of the empire. The biggest problem for the Germans was to save the German parts of Bohemia from being included in Czechoslovakia. The German members of the Reichsrat formed a National Assembly, and on October 30 they proclaimed the republic “German Austria” – a state without boundaries and form, which should have included all German Habsburg subjects. Thus, the free German Austria would blame the defeat on the Habsburgs, and free

Germany on the Hohenzollerns, two bygone dynasties, in the hope that they will be received in the ranks of other free nations.

By the end of October all the peoples of the Empire had abandoned the Habsburgs, establishing their own national states; only the Austro-Hungarian army, which defended the Italian territory, remained. Lost to the nationalist torrent, it also disintegrated. The Croatian regiments swore an oath to the south Slav state, the Czech regiments to the Czechoslovak Republic. The fleet flew south-Slav colours, seeking Yugoslav authority to avoid having to surrender to the Italians.

There was nothing left of the Habsburg monarchy. Charles was alone, with no authority whatsoever and he announced that on November 11 he was renouncing his rule of German Austria. On November 13, he did the same with regard to Hungary. He did not want to abdicate but he had to leave Vienna and Austria in 1919, carrying with him in exile all that remained of the once great empire.

Bibliography:

A.J.P. Taylor, Monarhia habsburgică 1809-1918 [The Habsburg Monarchy 1809-1918], Bucharest, ALLFA Publishing House, 2000.

Henri Prost, Destinul României: (1918-1954) [The destiny of Romania: (1918-1954)], Compania Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

The Count of Saint-Aulaire, Însemnările unui diplomat de altădată: În România: 1916-1920 [The testimonies of a former diplomat: In Romania: 1916-1920], Humanitas Publishing House, Bucharest, 2016.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa

Vai de steaua ta, Cipriane!Slovenii sînt slovaci, Karl e Charles iar frazarea și gratica, dăncileză sadea! Pun pariu că ești și doctor în istorie…

Cred că de fapt e vina traducătorului nu a celui care a scris articolul. Dacă te uiți scrie “translated by”.

Harta e incompletă Italia a rămas cu Trieste dar și cu alte porturi din peninsula Istria