The Central Powers were at their most favourable moment at the end of 1917. Russia had fallen prey to revolutions and the Bolsheviks, Lenin suing for peace. Russia’s exit from the war would have dramatic consequences for Romania, the only other Eastern European ally of the Entente, which was isolated and surrounded by the armies of the Central Powers. Even on the Western Front, things were going well for the Austro-Hungarians and the Germans. In such a situation, the military leaders in Berlin and Vienna were increasingly optimistic that they would win the war. However, the conditions were set for the situation to change drastically.

Despite the fact that the Ottoman Empire had lost Jerusalem to British troops shortly before Christmas, Lenin’s decision to withdraw Russia from the war had allowed the Ottoman Empire to regain control of Eastern Anatolia. A Turkish newspaper reported at the time: “The Russian revolution saved us from the immediate threat. As long as we do not lose sight of the importance of events in Russia and continue to watch them closely, we can calm down”.

The Battle of Caporetto

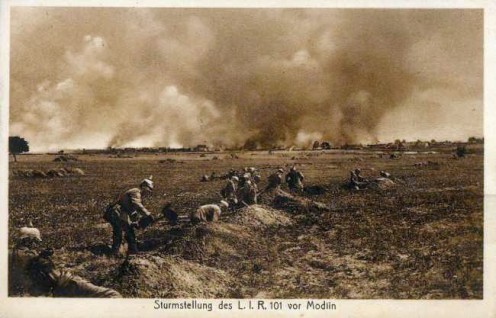

The Central Powers had taken the strategic initiative, following Russia’s and Romania’s exit from the war. This had happened after the Battle of Caporetto (October 1917), where Austro-Hungarian troops, aided by six German divisions, achieved a surprising success in the face of Italian forces. The attack was so strong that the Italian soldiers had to retreat chaotically, establishing a new defensive line north of Venice. The losses of the Italians were catastrophic. More than 30.000 Italian soldiers were killed or wounded, and 265.000 were taken prisoner. The shock was so great for the Italians that it led to the dismissal of the Chief of Staff and the fall of the government of Prime Minister Paolo Bosseli. However, the Italian army avoided total collapse at the last minute. Even so, many believed that Rome’s hope lay in concluding an honourable peace treaty without territorial losses.

Even though the United States had extended its declaration of war against Germany and Austria-Hungary in December 1917, less than 175.000 American soldiers had arrived in Europe. However, they will prove decisive in the summer of 1918, but until then nothing anticipated the outcome of November 1918.

The optimism of the Germans

Moreover, on November 11th, 1917, exactly one year before the end of the First World War and the fall of the Central Powers, Germany’s chief military strategist, General Erich Ludendorff, seemed optimistic: “Most likely, the situation in Russia and Italy will allow us to secure the western theater of war next year. About 35 divisions and 1.000 pieces of heavy artillery may be available for an offensive […]. Our general situation requires us to attack as early as possible, preferably in late February or early March, before the Americans bring their strong forces to bear”.

Colonel Albrecht von Thaer, another officer in the German General Staff, Colonel, wrote in his journal on December 31st, 1917: “Our position has never been so good. The Russian military giant is completely finished and pleads for peace; the situation is similar in the case of Romania. Serbia and Montenegro have simply disappeared. Italy is supported only with great difficulties by England and France, and we are entrenched in its best province. England and France are still ready for battle, but they are much more exhausted (above all the French), and the British are still under strong pressure from the German U-boat submarines”.

The haste of the Germans, justified

Undoubtedly, the German High Command was well aware that victory must be achieved quickly and had to seize the unexpected opportunity to be able to transfer 48 divisions from the East and send them into battle against the exhausted Allied soldiers on the Western Front. However, the unpleasant surprise for the Germans would come in the spring and especially in the summer of 1918, when the Allies, taking advantage of the contribution of US troops, took the strategic initiative that enabled them to win the war.

Bibliography:

Robert Gerwarth, Cei învinși. De ce nu s-a putut încheia Primul Război Mondial, 1917-1923 [The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917–1923], Litera Publishing House, Bucharest, 2017.

Margaret MacMillan, Făuritorii păcii. Șase luni care au schimbat lumea [Peace makers. Six months that changed the world], Trei Publishing House, Bucharest, 2018.

Glenn E. Torrey, România în Primul Război Mondial [Romania in the First World War], Meteor Publishing House, Bucharest, 2014.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa