For Romania, the First World War did not end on November 11, 1918. The Romanian army’s advance to Transylvania was made in stages, and until the end of January 1919, Romanian soldiers reached the Apuseni Mountains. On March 21, 1919, the Hungarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed, which profoundly disturbed the Allied powers, and especially Romania.

Bolshevik forces were already threatening Romania from the north and from the east, and now, the newly constituted Bolshevik Hungarian army began preparations for a military offensive in the west. On the night of April 15 to April 16, the Romanian troops stationed in the Apuseni Mountains were attacked. The counter-offensive of the Romanians was started soon after, and in only five days, Romanian troops managed to push back the Hungarians. The cities of Satu Mare, Carei, Oradea, Salonta fell, and on April 30, Romanian soldiers reached the Tisa River. Even so, military intelligence showed that Romania was still under the threat of a joint invasion by Bolshevik Russian troops in the north and east as well as by Bolshevik Hungarian troops.

US historian Glenn E. Torrey notes that: “Set firmly on positions along the eastern bank of the Tisa, the Romanians were faced with another decision. Some allied leaders, especially those in the French army, wanted the Romanian army to continue its advance on Budapest in order to disarm the Kun regime, which was creating bigger and bigger problems. The Romanians hesitated. They did not want to act alone and be accused of imperialism. They also had problems on its eastern frontiers, where renegade Romanian socialist Christian Rakovski, now Soviet commissar for Ukraine, threatened to invade Bessarabia. When his forces managed to drive out from Odessa the allied intervention forces in early April, this threat seemed credible. After transferring troops to the east, the Romanians held their positions on the Tisa during May, June and most of July, while the allied leaders in Paris tried to reach an agreement on how to resolve the situation in Hungary. The Romanian army rested during this period, while Kun and his military leadership turned their attention away from the eastern campaign on the Tisa, to the northern campaign against the Czech forces in Slovakia”.

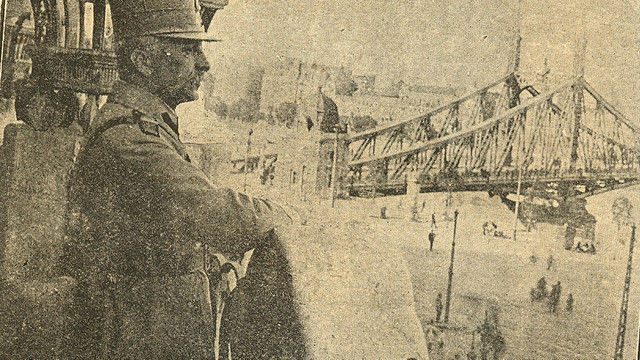

In the summer of 1919, Hungarian Command planned a major offensive against Romania, and it even considered making a junction with the Bolshevik troops in Ukraine. The offensive of the Hungarian army began on July 20, 1919 and managed to break through the Romanian defences. For a few days, the action of the Hungarian soldiers seemed to be successful. However, the Romanian Great General Headquarters decided on a counter-attack which sent the Hungarian forces into disarray. On July 27, 1919, the first Romanian troops crossed the Tisa and advanced towards Budapest. The first squadrons of the 3rd Roşiori Brigade, led by Colonel Gheorghe Rusescu, entered without firing a shot in the Hungarian capital on August 3. The next day, the troops of the 1st Vânători Division entered Budapest, and on August 18 paraded in front of General Gheorghe Mărdărescu, the commander of the Romanian troops from Transylvania, on Andrassy Boulevard.

“The cccupation of Budapest, a symbolic value”

Romanian historian Florin Constantiniu argues that: “The presence of the Romanian troops in the Hungarian capital was also a problem of prestige. When they entered Budapest on August 4, 1919, instead of a government controlled by Béla Kun, the so-called «syndicalist government» led by right-wing socialists Gyula Peidl and Károly Peyer, both hostile to the Communists, was in power ever since August 1. The occupation of Budapest by the Romanian army had a symbolic value for the Romanians: it was a compensation for centuries of oppression and humiliation endured in Transylvania. Without such satisfaction for the Romanian public opinion, the reconciliation between the two peoples and states would have been difficult. The occupation of Budapest was not an act of revenge (the Romanian military authorities had the right attitude and assisted the population with various humanitarian actions)”.

In fact, Romanian political figures such as Al. Vaida-Voevod considered that bilateral relations between the two countries should be on friendly terms: “The Hungarians were yesterday our enemies, today they are the ones vanquished and tomorrow we want for them to be our friends”.

Four months later, when the Romanian army withdrew from Hungary, the conservative forces, freed from the fear of communism, resumed the traditional policy of hostility towards Romania. In October 1919, Admiral Miklós Horthy, Hungary’s future regent, said: “Hungary’s number one enemy is Romania, because the biggest territorial claims are against it, and because it is the strongest of the neighbouring states. That is why the main goal of our foreign policy is to solve our problems with Romania by resorting to arms”.

Bibliography:

Glenn E. Torrey, România în Primul Război Mondial [Romania in the First World War], Meteor Publishing House, Bucharest, 2014.

Florin Constantiniu, O istorie sinceră a poporului român [A sincere history of the Romanian people], Encyclopaedic Universe Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008.

I.G. Duca, Memories [Memories], vol. I, Expres Publishing House, Bucharest, 1992.

Henri Prost, Destinul României: (1918-1954) [The destiny of Romania: (1918-1954)], Compania Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa