The victory of the Hungarian communist revolution led to the establishment of the first Bolshevik regime in Europe after the October Revolution in Russia. The de facto leader of the new regime was Béla Kun, the secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party and the foreign minister of the short-lived Hungarian Republic of Councils (March 21 – August 1, 1919). Even though the new regime legitimized itself through Marxist internationalist doctrine, the main objective of the new government remained to preserve Hungary’s territorial integrity, which led to inevitable conflicts with its neighbours.

A few days after the establishment of the communist government in Budapest, a new representative of the Entente, South African General Ian Christiaan Smuts, was sent to Hungary. He promised to help Budapest by proposing a new dividing line in Transylvania, which was more advantageous for Hungary, at the Paris Peace Conference. In return, Hungary had to stop its rearmament process. These more favourable terms were rejected without hesitation by Béla Kun.

In fact, Béla Kun was stalling to reorganize the army. The revolutionary rhetoric was temporarily abandoned by the regime and it started appealing to the patriotic sentiments of the troops. If at the moment the communists took over the power, the Hungarian army had about 20.000 people, its ranks were bolstered by an additional 50.000 to 60.000 volunteers. The Italians sold arms and ammunition to the Hungarian communists, motivated by their hostility toward neighbouring Yugoslavia.

After the Communists took power, the sporadic attacks of the Hungarian forces on the Romanian military and civilians in Transylvania intensified. In order to counteract the hostile actions of the Hungarian Bolsheviks, the Romanian government decided on a counter-offensive. Leading the operation was General Gheorghe Mărdărescu, who decided to start military operations on the morning of April 15.

According to General Mărdărescu’s testimony, on the eve of the Romanian offensive, the Hungarian forces numbered about 70.000 men, with 137 pieces of artillery and 5 armoured trains. Of these, about 20.000 soldiers and 72 artillery pieces were in the first line, and the rest in reserve. The infantry was better equipped and armed, having at their disposal numerous machine guns and submachine guns. Hungarian Bolshevik soldiers were led by former Austro-Hungarian army officers, who benefited from the experience of four years of war. However, the expected help from Bolshevik Russia did not come, due to the escalation of the civil war in the Ukraine between the Reds and the Whites.

In just two weeks, the Romanian army pushed the Hungarian troops beyond the Tisza River. At the beginning of May, the Hungarian government called for an armistice, committing itself to recognize the territorial claims of Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia in exchange for the ceasing hostilities. The Romanian side rejected this proposal, but did not continue the offensive beyond the Tisza River.

The collapse of the Bolshevik regime in Budapest

Taking advantage of the Romanian army’s decision to halt its advance, the Hungarian Bolshevik regime attacked Slovakia. The reasons were numerous, after the defeat at the hands of the Romanians, the communist government needed a moral victory, and a possible success would have cut the lines of communication between the Romanians and the Czechoslovaks, and would have opened a direct corridor to Russia.

TheHungarian offensive began on May 20. Overwhelmed by the initial attack of the Hungarian Bolsheviks, the Czechoslovaks asked the Romanians for help. The Great General Headquarters approved the request, and Romanian troops crossed to the west of the Tisza River and set up a bridgehead in the Tokaj region. The advance of the Romanians on the right wing of the Hungarian troops stopped the attack against the Czechoslovaks, but the latter’s counterattack was a failure. In this situation, the Romanian Great General Headquarters decided to stop the westward advance and defend the Tokaj bridgehead. The Czechoslovaks withdrew under the pressure of the Hungarian troops, breaking contact with the Romanians, which led the Great General Headquarters to decide to withdraw to the east of the Tisza River on the night of June 2 and to destroy the crossings over the river.

Despite their success against Czechoslovakia, the Hungarian Bolsheviks did not achieve the expected moral victory. On the contrary. Instead of incorporating the occupied territory in Hungary, the communists of Béla Kun imposed a puppet regime, proclaiming on June 17 the Soviet Republic of Slovakia with its capital in Prešov. This decision was a real blow to Hungarian nationalists, who supported the Bolshevik regime in hopes of rebuilding Hungary’s borders. Despite the victory over Czechoslovaks, the Hungarian Red Army began to disintegrate because of the tensions between the Bolsheviks and the nationalists.

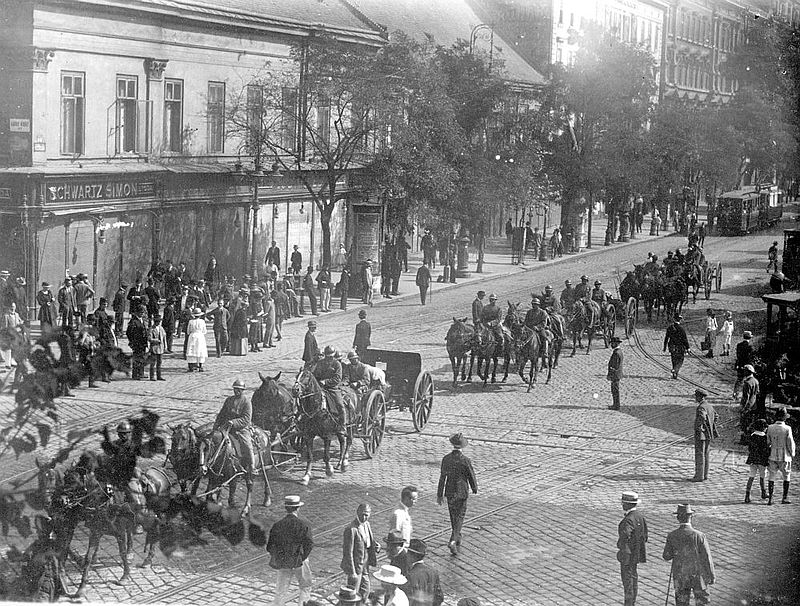

Taking advantage of the armistice with Czechoslovakia, the regime led by Béla Kun reorganized the army in order to prepare for an offensive against the Romanians. The attack began on the morning of July 20, all along the front line. After some initial successes, the Hungarian troops managed to cross the left bank of Tisa in several places, but the Romanian army managed to stabilize the front and stop the attack. This time, the Romanian soldiers were ordered to chase the enemy west of the Tisza River. The Romanian counter-offensive started on July 27. The advance was so rapid, that the Hungarian Bolshevik regime disintegrated in just a few days. On August 1, Béla Kun fled to Vienna, where he was arrested. On August 3, the Romanian army entered Budapest, occupying the Hungarian capital the next day.

Bibliography:

Oscar Jászi, The dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1929.

Margaret MacMillan, Făuritorii păcii. Șase luni care au schimbat lumea [Peace makers. Six months that changed the world], Trei Publishing House, Bucharest, 2018.

Peter Pastor, Hungary between Wilson and Lenin: the Hungarian revolution of 1918-1919 and the Big Three, Columbia University Press, New York, 1976.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa

Perché non si parla del Generale Rumeno Traian Mosoiu

Riporto da Wikipedia:

Le forze rumene hanno continuato la loro avanzata verso Budapest. Il 3 agosto, sotto il comando del generale Rusescu, tre squadroni del 6 ° reggimento di cavalleria della 4a brigata entrarono a Budapest. Fino a mezzogiorno del 4 agosto, 400 soldati rumeni con due cannoni di artiglieria hanno tenuto Budapest. Quindi la maggior parte delle truppe rumene arrivò in città e una parata si tenne attraverso il centro della città di fronte al comandante, il generale Moşoiu. Le forze rumene hanno continuato la loro avanzata in Ungheria e si sono fermate a Győr .