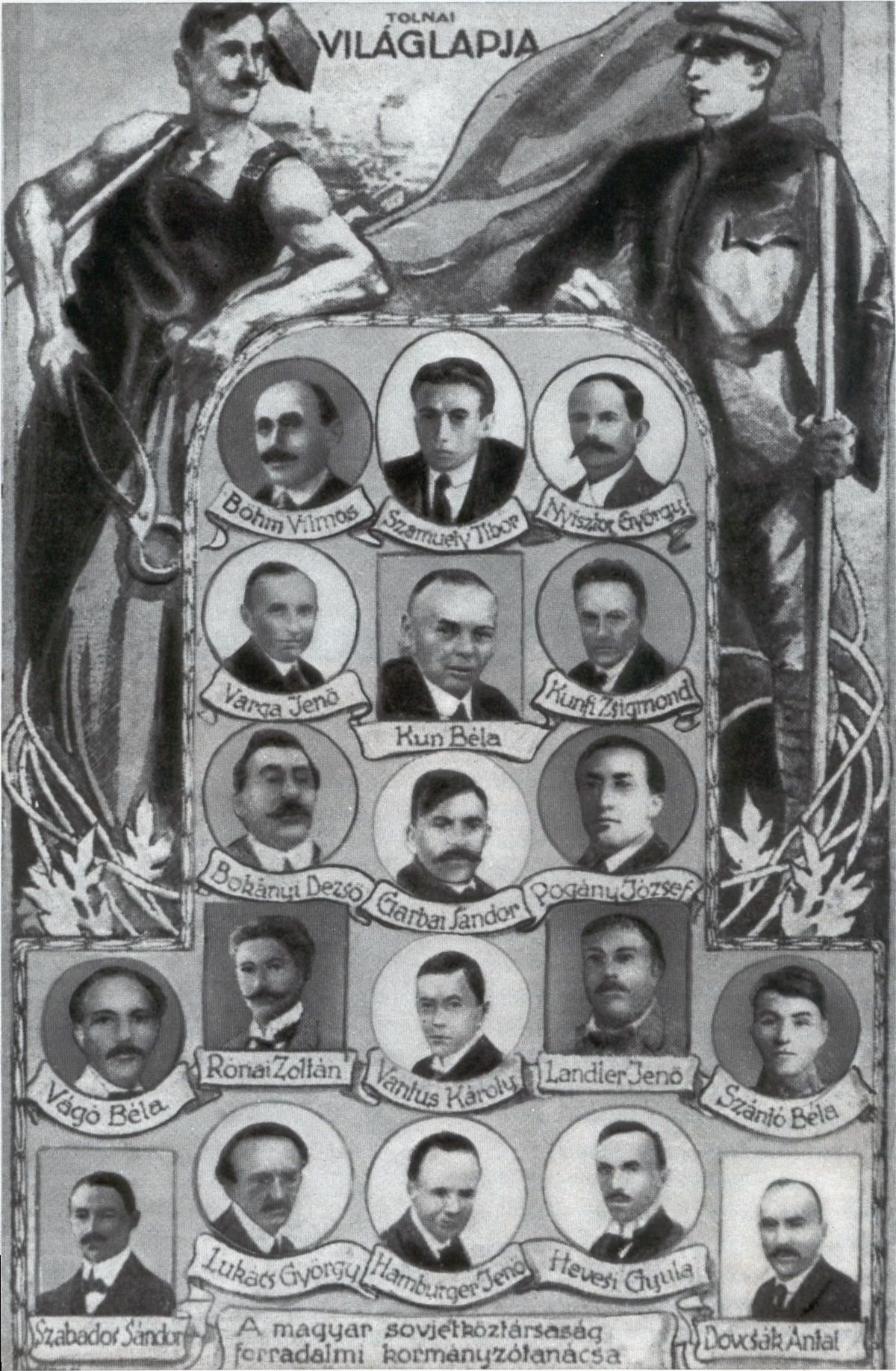

Bela Kun’s dictatorship lasted for half a year. Half a year in which the policies of the Bolshevik regime ruined the country. In a last ditch effort to regain popular support, the dictator rallied his armies against the Czechoslovaks and Romanians, wanting to take back the provinces Hungary had lost after the First World War.

In the summer of 1919, after a campaign of only three weeks, the Czechoslovaks were brought to their knees. This ensured that the entire military power of Hungary could then be unleashed against the Romanian troops dug in along the Tisza River.

The representatives of the Big Four proved to be on relative good terms with Bela Kun, being even willing to reduce Romania’s territorial demands, in exchange for the cooperation of the Bolshevik leader.

In this way, the border on the Tisza, the one promised by the Treaty of Bucharest, was denied to Romania. However, when the government received instructions from Paris that the troops had to be withdrawn from the Tisza River and brought to the new borders, it replied it will do so, only after the demobilization of the Hungarian army.Bela Kun refused.

The resumption of hostilities by the Hungarian army

Going against the will of the Great Powers, wishing to permanently resolve the conflict with the Romanians, Bela Kun ordered the troops on July 20 to attack the positions of the Romanian army on the Tisza River.The initial successes were quite surprising. Bela Kun was so confident that he sent a telegram to French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, saying he had crushed the Romanians.However, after three days of confrontations, not only did the Hungarian divisions fail to achieve victory, but they ended up surrounded, while the “hammer blows” of the Romanian army weakened their flanks.

Romanian troops then crossed the left bank of the Tisza, with the difference that, this time they did not stop there. Bela Kun’s forces were thrown in disarray, leaving the road to Budapest open. Thousands of soldiers were taken prisoner and Bela Kun asked in vain for the Allies to intervene. However, he already squandered any favour that he might have had. The Romanian advance continued and Bela Kun was forced to leave the country on August 1st.

Hungarian peasants came out to meet the Romanian troops, hoping that they would be finally liberated from Bolshevik terror. There were even nobles that received them with joy, as they were deprived of their ancestral privileges and titles.

Romanian soldiers in Budapest

On the night of August 3rd, the first units entered the capital, and on the following day, the bulk of the Romanian army entered Budapest. Residents received them with reserve. Some even cried when the troops started marching down Andrassy Boulevard. Starved and terrorized by the Bolshevik leadership, they now saw their country come under the occupation of the most unexpected of their opponents.

Romanian soldiers were taken aback with how, in a city as impressive as Budapest, the inhabitants lived from day to day.If we are to believe the statements of Major Nancovici, the representative of the Romanian commission in Budapest, in the absence of the Romanian intervention, the people would have been left without food in just a few days.

Kun’s brutal regime had alienated Hungarian peasants. Rather than being confiscated by the Bolsheviks, they preferred to hide their harvest, disrupting the supply to the cities. The markets were empty and the shops were closed and people were starting to eat fodder.The inhabitants of Budapest were so weak and pale that General Mărdărescu, the commander of the Romanian troops, said they looked like “a swarm of flies that fell into numbness because of their suffering”.

In the first days of the occupation, Romanian troops faced not only the food shortage, but also the institutional chaos caused by the Bolshevik regime and the power vacuum it left behind after its collapse. Gyula Peidl was tasked with creating a new government, under which the terms of the armistice were drafted. He remained in power until August 6th when Archduke Joseph replaced him with Istvan Friedrich, a well-known industrialist, as prime minister.

However, the archduke’s move is not seen with good eyes by the Allies. He supported the claims of the former Austro-Hungarian Emperor Charles I to restore the empire, despite that, his return to the throne, either in Hungary or Austria, could have triggered a new war.Archduke Joseph was eventually forced to resign on August 23rd, bringing down the whole government.

Romanian presence in the Hungarian capital was not approved by the Allies either. Their requests to stop the crossing of the Tisza River, and then to not occupy Budapest were disregarded one after the other.

The Allies eventually sent a military mission consisting of US General Harry Bandholtz, British General Reginald Gorton, French General Jean Graziani and Italian General Ernesto Mombelli to oversee the occupation of Hungary.

The industrialist Istvan Friedrich remained on the political scene and formed another cabinet, holding the position of prime minister during the entire period of occupation, but was strongly challenged by political forces inside the country.

The guardians of a broken country

Taking into account the unstable situation, General Mărdărescu, the commander of the troops and Panaitescu, the chief of staff, wanted to assure the people that although the war brought them to Budapest, it was one against the Bolshevik army and not against the common folk.In a proclamation, they emphasized the responsibilities of the Romanian soldiers as keepers of the peace and the integrity of the life of every Hungarian citizen.General Holban was then appointed as governor of Budapest, receiving, among other things, the difficult task of improving the conditions in Budapest.

Plenipotentiary minister Diamandi is sent by the Romanian government as High Commissioner to renew diplomatic relations with the new Hungarian government and to deal with other officials sent from Paris.

In the meantime, Romanian divisions continued to advance. They maintained order, confiscated firearms and disarmed the remnants of the Bolshevik army in the rest of the country.

Jurnal de Operațiuni al Comandamentului Trupelor din Transilvania (1918-1921), [Operations Log of the Troop Command in Transylvania (1918-1921)], vol. I and II, Viorel Ciubota, Gheorghe Nicolescu și Cornel Tuca, Satmar Museum Publishing House, Satmar, 1998.

Radu Cosmin, Românii la Budapesta [Romanians in Budapest], “Moise Nicoară” Foundation Publishing House, Arad, 2007.

Constantin Kirițescu, Istoria războiului pentru Întregirea României: 1916-1919 [The history of the war for the unification of Romania: 1916-1919], Scientific and Encyclopedic Publishing House, Bucharest, 1989.

Harry Hill Bandholtz, Major General Harry Hill Bandholtz: An Undiplomatic Diary, edited by Andrew L. Simon, Columbia University, 1933.

Charles Upson Clark, United Roumania, Dodd Publishing House, Mead and Company, New York, 1932.

Gheorghe Mărdărescu, Campania pentru desrobirea Ardealului și ocuparea Budapestei [The campaign for the liberation of Transylvania and the occupation of Budapest], Cartea Românească Publishing House, Bucharest, 1922.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa