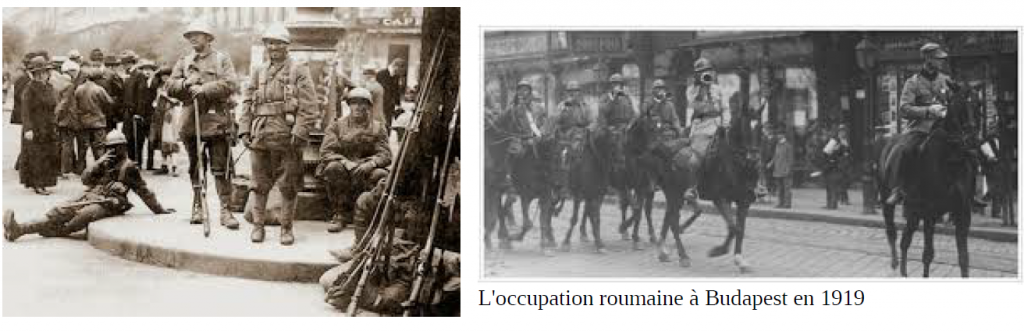

Major Nancovici, an envoy of the Romanian commission in Budapest, drew up a brief report on the state of the Hungarian capital after the first few days of occupation.

Surprisingly, while people were starving, the Bolsheviks had gathered in the ”Hungarian Discount and Exchange Bank”, the largest warehouse in the city, significant quantities of food. Romanian soldiers immediately opened this warehouse to the public, as well as other smaller ones scattered all around the city.

More than 700.000 kilograms of sugar, 700.000 cans of meat, 650.000 kilograms of salt, 400.000 litres of oil, 170.000 kilograms of wheat, 70.000 kilos of millet, 50.000 kilograms of bran are offered to the inhabitants. Even so, for the nearly two million hungry people that was insufficient. The major also pointed out that the most delicate problem was that of meat, considering that it would require almost 3.000 cattle every week to cover the needs of the inhabitants. However, in just a few days, supply was re-established and meat was brought in twice a week.

In order to facilitate the transport of various products to Budapest, special supply trains were created, which stopped along Hungary and were loaded with necessary foodstuffs. Moreover, rail and freight transport started again, with a watchful eye especially on travellers. The Bolsheviks, though scattered, were still a force. There were even rumours that more than 50.000 Bolshevik supporters were waiting for the withdrawal of the Romanian army to yet again seize power. There were attacks on isolated Romanian troops, like the one against the unit led by sub-lieutenant Dodu of the 6th Roșiori Regiment. He and his men were killed during an ambush.

Lines of communication were restored, but only the institutions of the Hungarian state and the Romanian army could make use of them. Phones were confiscated and access was restricted to hamper the organization of those still loyal to the Bolshevik cause.

The restoration of liberties

Completely suppressed during the Bela Kun regime, the press gains some freedom, but under the strict supervision of the censors. Over two dozen publications see the light of day once more.

The right to assembly is instituted, over 15.000 people participating in different manifestations and public debates, but which were done only with special authorizations and with the prior notification of the authorities.

Solving the food crisis

Countless children flocked to the garrisons of the Romanian soldiers, because they usually shared their rations with them. Over a dozen field kitchens were set up offering food to over four thousand people every day. The local officials of Rakosz Palota commune wanted to personally thank a Romanian regiment for taking care of nearly 300 orphans.

However, Lieutenant-Colonel Cristea Vasilescu, the chief of the General Staff of General Holban, talks about the ill will and corruption that made the tasks entrusted to the Romanian command installed in Budapest difficult. The employees of the Hungarian food ministry, being tasked with procuring products for the capital, were largely irresponsible, wanting to profit off of people.

Profiteering blossomed. Food was stored and then sold at exorbitant prices to the population. Such was the case of the “Haditelmin” company, which stored over 90.000 kilograms of meat. The same ministry did not allow the purchase of grain from individuals, but only from local companies, and the flour that was then put on sale had a high price, of over 25 crowns per kilogram. However, Romanian command did not let this situation continue and broke the monopoly of these companies, and consequently the price decreased. It also introduced a tithe for the mills because the Hungarian food ministry’s agents did not pay the wheat taken from the peasants, so they began to hide it again, as in Kun’s time. Through the tithe, the resulting products were bought by the Romanian command and eventually sold to the inhabitants of the capital at reasonable prices.

Moreover, corrupt officials were replaced by Romanian agents, specially delegated to take over their tasks. They strove to gain the confidence of peasants to hand over their hidden foodstuffs in exchange for fair compensation. The fact that around Budapest forty communes were exempt from requisitioning allowed the daily transport of dozens of wagons with surplus food products. It was even requested to collect the excess products from Romania.

To the east of the Tisza River, Romanian command had prepared nearly 10.000 wagons with wheat, potatoes and firewood to be transported. However, the food ministry refused to provide the necessary locomotives, on the grounds that they did not have enough and tried to hide that 500 locomotives were withdrawn to Szombothely. Confronted with this fact, they still refused, not trusting the promises of the Romanian army not to requisition them afterwards.

The issue of requisitions

Indeed, requisitions had taken place according to the terms of the truce imposed since the beginning of the occupation, involving half of the rolling stock, one third of the livestock and one third of the agricultural machines. Hungarian armaments and ammunition factories were also turned over and disassembled, with all the parts and machinery loaded in wagons and then sent back to Romania. It had been also decided that the expenses of the Romanian occupation army should be borne by the Hungarian state.

The conditions, although harsh, were on the one hand key to neutralizing the military power of an hostile nation and on the other, a compensation for the extensive damage done through the confiscations of the Central Powers, which followed the signing of the Treaty of Bucharest.

However, the Hungarian government’s propaganda exacerbated the scale of these requisitions. Reports from the capital, like the one from October 9th, when the Allied comission informed the war council in Paris that 50% of all locomotives and 90% of all freight wagons were taken from Budapest caused serious concern.

Romanians were accused of having plundered the entire country, that only paving stones remained. That they stole everything that could be taken, from furniture to silverware, from paintings to telephones. Gyula Pekar, secretary of state in the Ministry of Education, said that the robbery committed by Romanians was unparalleled in the history of the world.

Jurnal de Operațiuni al Comandamentului Trupelor din Transilvania (1918-1921), [Operations Log of the Troop Command in Transylvania (1918-1921)], vol. I and II, Viorel Ciubota, Gheorghe Nicolescu și Cornel Tuca, Satmar Museum Publishing House, Satmar, 1998.

Radu Cosmin, Românii la Budapesta [Romanians in Budapest], “Moise Nicoară” Foundation Publishing House, Arad, 2007.

Constantin Kirițescu, Istoria războiului pentru Întregirea României: 1916-1919 [The history of the war for the unification of Romania: 1916-1919], Scientific and Encyclopedic Publishing House, Bucharest, 1989.

Harry Hill Bandholtz, Major General Harry Hill Bandholtz: An Undiplomatic Diary, edited by Andrew L. Simon, Columbia University, 1933.

Charles Upson Clark, United Roumania, Dodd Publishing House, Mead and Company, New York, 1932.

Gheorghe Mărdărescu, Campania pentru desrobirea Ardealului și ocuparea Budapestei [The campaign for the liberation of Transylvania and the occupation of Budapest], Cartea Românească Publishing House, Bucharest, 1922.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa