When the First World War broke out, Romania had been a member of the Triple Alliance since 1883. However, for the first two years of the conflict it stayed out of the war. In this context how did the military leaders in Berlin react to Romania’s neutrality?

Besides King Carol I, only a handful of Romania’s political leaders knew about the country’s commitment to the Triple Alliance. It was not brought to the attention of the public because of the overwhelming pro-French sentiment of the society at large, but also because of the way in which Hungary treated the three million Romanians in Transylvania.

Starting with 1907, Bucharest began to slowly but surely distance itself from the Triple Alliance. Just a month before the conflict began, King Carol I of Romania warned his allies in Berlin and Vienna that it would be impossible for him to mobilize the Romanian army because “the issue of Romanians in Transylvania stirred up anti-Hungarian sentiments on the part of the Romanian population”.

The Crown Council of Sinaia convened on August 30, 1914 by King Carol I decided to proclaim the neutrality of Romania. It was a blow for the Central Powers and after the death of King Carol I in October 1914, the political and military leaders in Vienna and Berlin no longer had any illusions about a possible entry of Romania on their side. The Romanian society, the vast majority of Romanian politicians and the new queen of Romania, Marie, supported the Entente. All that the leaders of the Central Powers could hope for was for Romania to remain neutral, but they also considered the idea of attacking Romania as early as the spring of 1915.

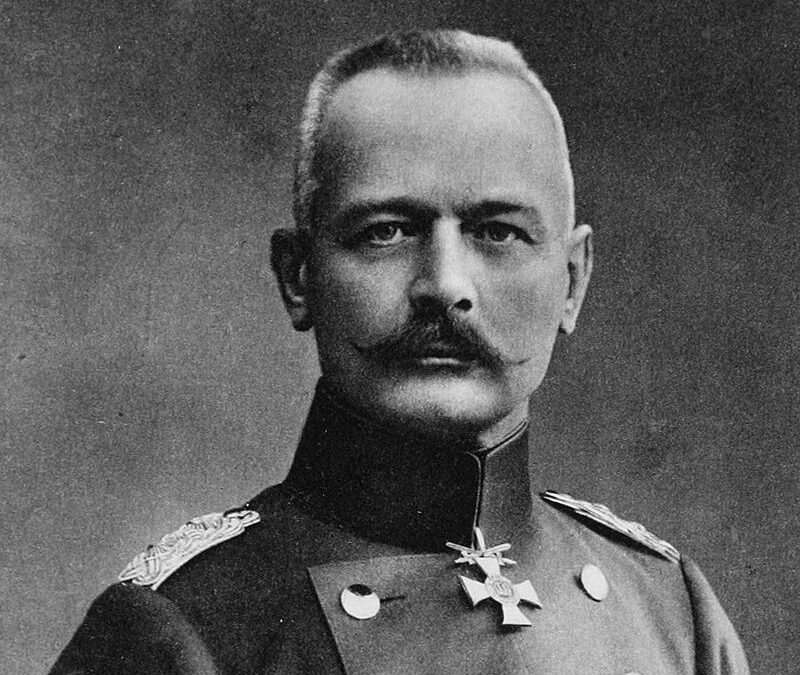

Romania in Falkenhayn’s memoirs

The memoirs of General Erich von Falkenhayn, the chief of the German General Staff from 1914 to 1916, sheds light on the attitude of the Central Powers towards Romania. Falkenhayn notes that since the fall of 1914, German military leaders were no longer convinced that Romania would join the Central Powers and they raised the issue of attacking Romania in early spring 1915, as the officials in Bucharest were making it hard for German armament to reach Turkey. However, it was considered that “as long as the Russian pressure was exercised with maximum force in Hungary and Galicia, an operation against Romania and through Romania was not possible. The necessary forces could not be made available, although it was appreciated that, given the lack of weapons and munitions in the Romanian army, its capacity for resistance was significantly reduced”.

Falkenhayn states that at the end of the summer of 1915 the problem of opening a road to the south-east was raised again and it had to be decided whether this would be done through Serbia or Romania. With the entry of Bulgaria into the war on the side of the Central Powers and the surrender of Serbia this dilemma was resolved, but a new one appeared. Bulgaria’s willingness to attack was restrained only by the inability of the Bulgarian army to wage a war on two fronts, against Romania and Greece.

Over time, Romania’s hard line stance regarding the transit of German weapons to Turkey was also toned down. But in January 1916, after the visit of Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria to the German General Staff, it was agreed that Romania would be given an ultimatum.

Falkenhayn says he had given up on the idea of transmitting the ultimatum for two reasons. Firstly, because the Bulgarian troops on the Thessaloniki front suffered great hardships, without even considering the difficulty of transporting them from Thessaloniki to the north, on the border with Romania. Secondly, Romania fulfilled its economic obligations with Germany impeccably. “Were the Central Powers able to endure that year of 1916 without the food and oil provided by Romania? Would Germany have been able to support the Western Front on the Meuse and the Somme if its few reserves had been sent to the Black Sea?” Falkenhayn wondered.

Romania’s entry into the war, determined by an event that “could not have been foreseen”

Regarding the moment of Romania’s entry into the war Falkenhayn wrote the following: “Romania’s entry into the war on the side of the Entente could not have been foreseen nor anticipated: the break through on the Austro-Hungarian front in the summer of 1916, under the conditions in which, on the eastern theatre of operations, the Russians did not have numerical superiority”. Falkenhayn refers to the offensive of the Russian troops led by General Brusilov, launched on June 4, 1916 which brought the Russians close to the Cârlibaba Pass in the Eastern Carpathians.

Bibliography

Sorin Cristescu, Misiunea contelui Czernin în România [Count Czernin’s Mission in Romania], Military Publishing House, Bucharest, 2016.

Glenn E. Torrey, România în Primul Război Mondial [Romania in the First World War], Meteor Publishing, Bucharest, 2014.

I.G. Duca, Memorii [Memories], vol. I, Expres Publishing House, Bucharest, 1992.

Henri Prost, Destinul României: (1918-1954) [The destiny of Romania: (1918-1954)], Compania Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa