Passing through the most difficult moment of its history, losing more than half of its troops and two-thirds of its territory, the Romanian army underwent a process of rehabilitation, reorganization and rearmament in early 1917. This process was a success and prepared the Romanian army well above the expectations of its opponents.

Even though the 1916 disaster was barely averted, the leadership of the Romanian army leadership was eager to plan offensive actions, not only to speed up the liberation of the country, but to also protect its position in the allied coalition. However, within the Romanian Armed Forces, there was yet again a battle of egos between the Chief of the Romanian General Staff, General Constantin Prezan and the commander of the Romanian Second Army, General Alexandru Averescu. It was only natural that the two came before King Ferdinand with two different offensive plans. Prezan’s plan envisioned an offensive to the west of Siret, in the Nămoloasa area in cooperation with the Russian Fourth Army by the new First Romanian Army. Meanwhile, the Romanian Second Army would carry out a secondary offensive through the Oituz pass to Transylvania. Averescu reacted to this plan calling it “lunacy”. Instead, Averescu proposed another plan. The Second Army led by him, strengthened with several other divisions would attack in the south to the Putna River, in the general direction of Focșani and Buzău.

The Russian High Command (the STAVKA) would change its attitude regarding the role that the Romanian Army will play in any future offensive actions. The radical change was determined by the impact of the February Revolution on the Russian army. The participation of soldiers’ councils in Russian decision-making, the democratization and the abolition of punishments led to the reduction of Russian officers’ authority among their own soldiers. The weakening of discipline among Russian soldiers made way for revolutionary speeches, and more and more soldiers demanded peace and refused to obey the orders that were given by their officers.

The Chief of the Romanian General Staff, General Constantin Prezan, also noticed the collapse of the morale of the Russian army in the spring of 1917 and the lack of discipline in its ranks. Prezan asks Berthelot to try and convince the leadership of the Russian army of the necessity for the offensive to begin as early as possible. Berthelot also wrote to Paris: “The only way for the Russian army to rid itself of indiscipline is to send it into the fire of battle”.

For the Romanian Front, the STAVKA approved a plan made by Russian General Nikolai Golovnin, which was compatible with the view of the Chief of the Romanian General Staff, Constantin Prezan, who envisioned an attack in the Nămoloasa area.

Operational instructions were given on June 1, 1917. The Romanian army had “to attack and break through at all costs” the lines of the German Ninth Army to the west of the Nămoloasa bridgehead in the direction of Râmnicu Sărat to encircle the enemy’s rear-guard. The Romanian Second Army was ordered to attack the right wing of the Austrian First Army and to advance on the upper valley of the Putna river to threaten the main lines of communication between the two enemy armies. The Russian Fourth Army, located between the two Romanian armies, had to break through the enemy front at Ireşti and head towards Focșani to make the junction with the Romanian army in order to destroy the enemy forces between the Siret river and the mountains. In the south, the Ninth and Sixth Russian armies had to conduct local offensive actions to cover the advance of these three armies. The offensive had to start between June 12 and July 14, but delays in preparation pushed the date of the attack to July 24. Romanian General Alexandru Averescu had his own apprehensions regarding this plan, especially since it was similar to that of his rival, General Constantin Prezan

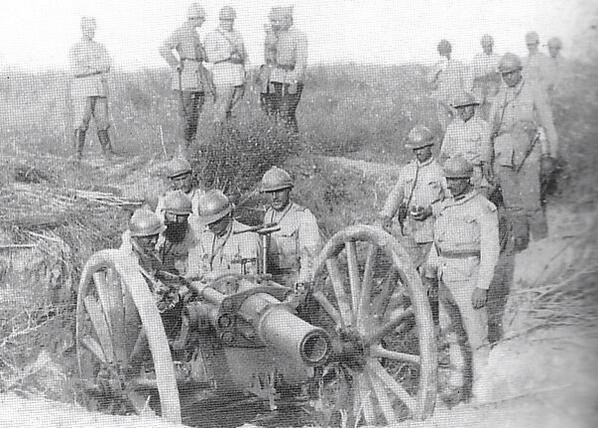

A “new army”

The Romanian army in the spring of 1917 was radically different from the one in the autumn of 1916. The endowment with modern arms and ammunition was followed by a careful instruction in their use with the help of the members of the French Military Mission in Romania. After the reorganization of the Romanian army, combat forces reached over 400.000 men. At the end of April 1917, a new Romanian army was present on the battlefield. It wasn’t as large as the one mobilized in August 1916, but it was now more flexible and better equipped. The core of it was the Romanian First and Second armies.

The rising morale of the Romanian troops after rebuilding and reorganization was also noticed by Russian General Monkevitz, Chief of Staff of the Russian Fourth Army on the Romanian front. He described the sad state of the Russian troops in relation to the Romanian ones in the summer of 1917: “Among the Romanian regiments, that were preparing to attack at the same time as ours, things were going rather differently. A great warlike ardour emboldened the reinvigorated and strengthened army: the officers and soldiers were eagerly waiting for the battle, to avenge their uninterrupted failures, and liberate the invaded territory”.

Selective bibliography:

Glenn E. Torrey, România în Primul Război Mondial [Romania in the First World War], Meteor Publishing House, Bucharest, 2014.

I.G. Duca, Memorii [Memoirs], vol. I, Expres Publishing House, Bucharest, 1992.

Henri Prost, Destinul României: (1918-1954) [The destiny of Romania: (1918-1954)], Compania Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

The Count of Saint-Aulaire, Însemnările unui diplomat de altădată: În România: 1916-1920 [The testimonies of a former diplomat: In Romania: 1916-1920], Humanitas Publishing House, Bucharest, 2016.

Constantin Argetoianu, Memorii [Memoirs], Humanitas, Bucharest, 1992.

Florin Constantiniu, O istorie sinceră a poporului român [A sincere history of the Romanian people], Encyclopaedic Universe Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa