Just seven months before the Great Union of December 1, 1918, Romania was at its lowest moment in history.

With most of the country occupied and with a Bolshevik revolution that led to the collapse of the giant Russian Empire, that capitulated at Brest-Litovsk, Romania was obligated to accept the humiliating conditions imposed by the Central Powers and to sign a peace treaty that formalized the loss of its independence.

The dream of freeing the Romanians from over the Carpathians had turned into a terrible nightmare. The words of the French Ambassador to Romania (1916-1920), the Count of Saint-Aulaire, are perhaps most eloquent about the suffering suffered by Romania: “If I try, by sketching it only, to evoke the icon of the suffering that overwhelmed Romania, for a place in an imaginary museum of moral beauties, I should put this country, whose virtues rise at the height of suffering and even higher, in the hall of masterpieces.”

The summer of 1918 was a summer of pain for the Romanians, attenuated only by the determination of King Ferdinand not to ratify the dishonourable peace with the Central Powers. Hope for Romania came from the Western front. The military and economic superiority of the Entente began to take its toll. Germany could not cope with the military pressure, nor with the worker strikes that were eating at its core.

Confronted with a strong economic crisis because of the war, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was also starting to fall apart.

Romanians in the dying empire were obstinate that it was time to decide their own future. On October 30 the Romanian National Council (RNC) was established, becoming the only political body of the Romanians in Transylvania and Hungary. A few days later the RNC addressed to the Entente Powers a manifesto stating that the Romanian parts of Transylvania, Banat, Crişana and Maramureş are separate from Austria-Hungary and that they “now form with Romania a single, free, independent state. We declare irrevocably the desire of the inhabitants of these regions to become and to remain citizens of Greater Romania”.

Meanwhile, on November 10, Romania re-enters the war less than 24 hours before the truce on the Western Front was signed. Time had no more patience, and the events in the provinces inhabited by Romanians in the Austro-Hungarian Empire precipitated. The Hungarians last try to make the Transylvanian Romanians deviate from the road of unification fails on November 15, 1918, the day when the RNC decides to convene a large National Assembly in Alba Iulia to resolve upon the fate of the Romanians in Transylvania. The summons drafted by Vasile Goldiş, had a strong impact: “In the name of eternal justice, the Romanian nation has to have a say regarding its fate. For this purpose, we convene the National Assembly of the Romanian nation in Alba Iulia, the historic city of the nation, on Sunday, December 1, 1918, at ten o’clock”. In Bukovina, the provincial National Congress decided on November 28 “the unconditional and eternal unification of Bukovina in its old frontiers, up to Ceremuș, Colacin and Nistru, with the Kingdom of Romania”.

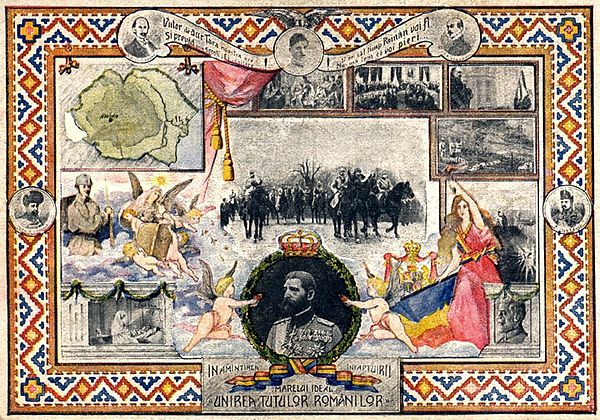

The road to achieving the Great Union was now open, and the Great National Assembly of Alba Iulia embodied the most wonderful page of Romanian history.

The unification of Transylvania

On November 15, 1918, the Romanian National Council decided to convene a large National Assembly in Alba-Iulia to resolve upon the fate of the Romanians in Transylvania. The mobilization of the masses was obviously done first and foremost through the Romanian press of the time: “Come all to the Great National Assembly that will be held on December 1 in the Belgrade of Michael the Brave. Come in the thousands and tens of thousands! Leave your worries at home this day, for on this day we will lay the foundation of a good and happy future for our entire Romanian nation”. And indeed, there were good days before December 1, all the roads and trains were filled with Romanians who came to their nation’s greatest gathering. The trains were adorned with green fir branches and national flags. In addition to the 1228 official delegates from all areas of Transylvania, invested with so-called credentials, a kind of empowerment that allowed them to participate directly in the debates in the Hall of the Union and to vote, there were over one hundred thousand Romanians, many from the neighbouring areas that eventually filled the Roman Plateau near Alba Iulia, the place where the Transylvanian Romanian assembly was to be held.

The unanimity of those present called for the document of Union with Romania to be voted in its entirety. “Is the Honourable Assembly in agreement with the Resolution?” A thunder of acclamations erupted in unanimous approvals: “We want a single Romania, of all Romanians!” The echo of the acclamations in the hall reverberated outside the hall in the cheers of the tens of thousands of Romanians that welcomed the Resolution presented by Vasile Goldiş.

“The greatness ( ed. of realizing Greater Romania) lies in the fact that the completion of the national unity was not the work of any political man, of any government, of any party; it was the historical deed of the entire Romanian nation, carried out with a strong impetus that burst from the depths of the consciousness of the unity of the nation, an impetus controlled by political leaders and guided with remarkable political intelligence towards a desired goal”, in the words of historian Florin Constantiniu.

Selective bibliography:

Henri Prost, Destinul României: (1918-1954) [The destiny of Romania: (1918-1954)], Compania Publishing House, Bucharest, 2006.

Florin Constantiniu, O istorie sinceră a poporului român [A sincere history of the Romanian people], Encyclopaedic Universe Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008

I.G. Duca, Memorii [Memories], vol. I, Expres Publishing House, Bucharest, 1992.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa