Immediately after the end of the First World War, the myth spread in Germany that the Imperial Army had not lost the war on the front, but that it had been betrayed by civilians, especially the Republicans who overthrew the monarchy. According to this myth, the German leaders who signed the November 11 Armistice were considered traitors – “the November criminals” – and that the Weimar Republic, created later, was the work of these criminals who had betrayed the army and, implicitly, the country in order to gain power.

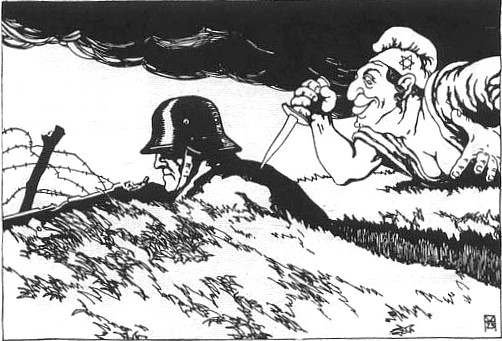

This myth of betrayal spread to right-wing circles of inter-war Germany, especially among the militants disappointed with the way the war ended and the terms imposed on Germany by the November 1919 Peace Treaty. The Nazi Party subsequently contributed to the propagation of this myth, using it to discredit the image of the Republic of Weimar, described as a corrupt, immoral government led by the “November criminals”, mostly Jews and Marxists, that were responsible for the disaster of the country.

The emergence of the myth was possible due to events from within the German military ranks. The General Staff informed Kaiser Wilhelm, at the end of September 1918, that the country was in a dire military situation.

Ludendorff then argued that he doesn’t guarantee that the front will hold for more than 24 hours. He therefore urged the civil government to contact the Entente to immediately request an armistice, and recommended that Woodrow Wilson’s terms be accepted (the 14 points). If until then the generals had virtually ruled the country and the war effort, as they held a great deal of influence on the Kaiser, after the failure of the offensive on the Western Front, they decided to relinquish power to civilian leaders. Thus, the army placed all responsibility for the capitulation and its consequences on the civilian leadership and government, excluding the military entirely from the equation. Later, Ludendorff stated that Germany cannot accept the terms demanded by the Allies and that the war- which he had previously stated that it was lost- must be continued.

After the end of the war, Ludendorff played an important role in propagating the myth of betrayal. He accused the government of Berlin, but also the population, for the surrender, and argued that the military – who wanted and could have continued the war! – lacked support. The idea could seem plausible since, at the time of the Armistice, the German army was still in enemy territory (in Belgium and France), and Berlin was not immediately in danger of being occupied. Thus, the military could easily argue that they could have continued the struggle and that defeat was not imminent. Further studies have shown, however, that the German army was facing serious supply problems at the time, and that by the end of 1918 it was already overwhelmed on the Western Front.

The myth gained even more supporters after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, which the Germans perceived as an unfair “dictate”. The right-wing circles in the new Republic of Weimar- conservatives, nationalists, former soldiers – harshly criticized the peace terms and, implicitly, the government that had signed it. The Right claimed that Socialists, Communists and Jews were responsible for the disaster, because they had not supported the war, even yet, they played a role in betraying Germany.

Historian Richard Hunt described this myth as an irrational belief born out of a sense of common shame, but not because Germany had caused the war but because it had lost it. He believes that it was not the blame for instigating the war that played an important role in Germany’s post-1918 national psychology, but the shame of weakness, of defeat.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa

Author Andreea Lupsor

Always the Jews!

The same, now destroying the world!