The Duchy of Bukovina, which was a part of Austria-Hungary since the establishment of the Double Monarchy, from 1867 until 1918, represented the northern part of medieval Moldavia. The Habsburg Empire occupied this territory in 1775, and on November 28, 1918, due to the fall of Austria-Hungary, following the defeat in the First World War, the representatives of the Romanians in Bukovina unanimously voted “the unconditional and everlasting union” with Romania.

In fact, this land was the place of birth and the centre of power and culture of the Moldavian medieval state. The necropolis of Moldavia’s first Moldavian voivodes, Suceava, and the most important Moldavian medieval monasteries, Moldovita, Sucevița, Voroneț and Humor, were on the territory occupied by the Habsburg Empire in 1775, after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774, that was concluded by the signing of the Kuchuk-Kainarji Peace Treaty (July 21, 1774).

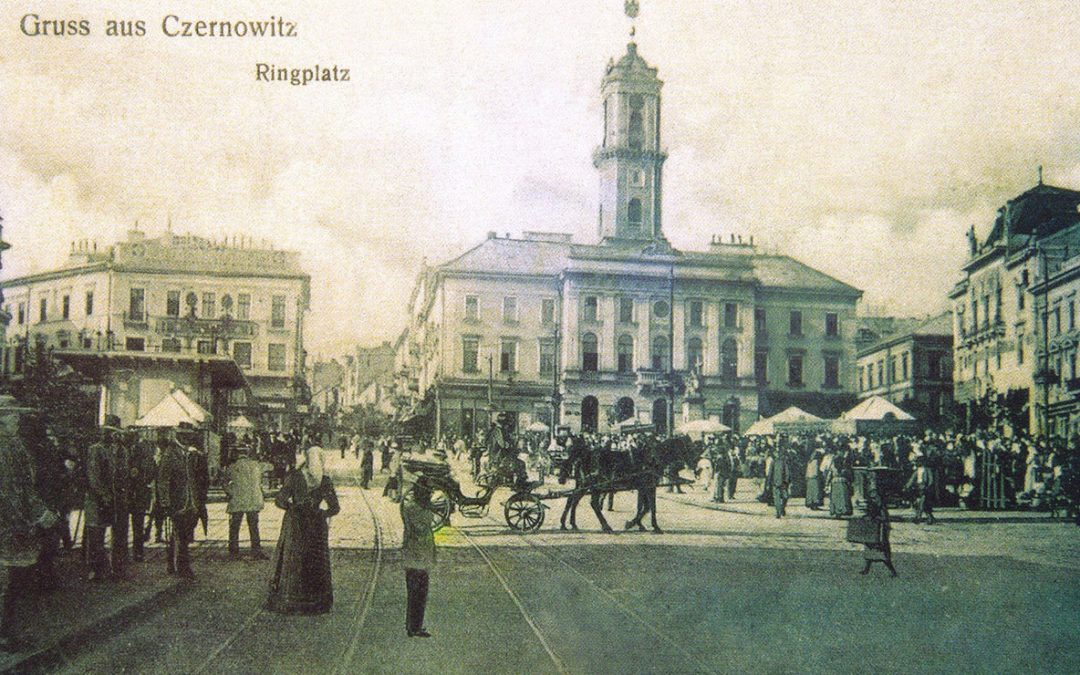

Initially, different toponyms were used for the province’s name, including “Austrian Moldavia” to distinguish it from “Turkish Moldavia” or “Suceava County”. In time, in order to forget the connection with Moldavia, the name “Bukovina” was adopted, from the word Slavic “buc”, meaning “beech forest”.

After more than a century of Austrian rule, on the verge of the First World War, Bukovina had become a multi-ethnic province. The percentage of Romanians, which represented the overwhelming majority of the population at the time of annexation, decreased in 1910 to 34.4%, out of the 800.000 inhabitants of Bukovina. Over time, the persecution of the Orthodox Romanians by the Austrian administration had led many to leave the province and head to Moldavia. In the meantime, Austrian domination encouraged many emigrants to settle in Bukovina. They were part of different ethnic groups: Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Jews, Austrians, Germans, Armenians, Poles, Slovaks, etc.

Romania entered the Great War on August 14, 1916, with the clear objective of occupying the Romanian inhabited territories of Austria-Hungary: Transylvania, Banat, Crișana, Maramureș and Bukovina. In spite of the military failures and the humiliating Treaty of Bucharest (7 May 1918), the road to this goal was opened in a surprising manner.

The second province that united with Romania

Following the dissolution of the Russian Empire, Bessarabia, the eastern half of Moldavia, occupied by Russia ever since 1812, united with Romania on April 9, 1918 after a vote in the Country Council of Chișinău. The second step in the realizing of Greater Romania objective would be taken by Bukovina.

During the conflict, the territory of Bukovina was sharply disputed, it being occupied by the Russians on three occasions and as many times recovered by the Austrians. The Vienna authorities took harsh measures against the Romanians and Ruthenians from Bukovina after 1916, going so far as to execute those suspected of treason in favour of the Russians or Romanians. An example in this respect, immortalized by the writer Mircea Streinul, in a novel published in 1938, was the tragedy of a 15-year-old child from the village of Cuciurul Mare, Ion Aluion, hanged by an Austrian gendarme after being suspected of betrayal because he was seen on the edge of the village talking with a Russian reconnaissance patrol.

The process of disintegration of Austria-Hungary at the end of the First World War lit up national energy in Bukovina. Unlike Bessarabia, a province mostly inhabited by Romanians, obstacles emerged in Bukovina against the realization of the union with Romania, due to the aggressivity of Ukrainian nationalists and the divisions among the Romanian elites. The Romanian unionist movement was led by Iancu Flondor, but the Ukrainians also benefited from the support of a Romanian, Aurel Onciul.

On October 27, 1918, the Romanian National Assembly convened in Cernăuți, which declared itself the Constituent Assembly of Bukovina and decided on “the unification of Bukovina with the other Romanian countries in an independent national state”. The Assembly avoided the wording “union with Romania”, because at that time Vienna was still in the war, and Romania had signed peace with the Central Powers.

The Romanians of Bukovina formed a National Council, composed of 50 members, headed by Iancu Flondor. Confronted with the risk of the province’s division, because of the aggressiveness of the Ukrainians who had organized their own paramilitary formations, Flondor requested the Romanian Government’s help to restore the order. The new Romanian Prime Minister, General Constantin Coandă, decided to accept this request and sent a division to Cernăuți, led by General Iacob Zadika. On November 11, 1918, on the very day that the armistice which ended the Great War was signed at Compiègne, Romanian troops entered Cernăuți.

Later, on November 28, in the marble hall of the Cernăuți Metropolitan Church, the General Assembly of Bukovina met to “establish the political relationship of Bukovina with the Romanian Kingdom”. Unanimously, the Congress voted “the unconditional and everlasting union of Bukovina, in its old frontiers, to Ceremuș, Colacin and Nistru, to the Kingdom of Romania”.

On December 19, 1918 the Royal Decree 3774 enters into force, the first article of which reads: “Bukovina in its historical boundaries is and remains united with the Kingdom of Romania”. The act by which Bukovina united with Romania was recognized internationally by the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (September 10, 1919), signed by the Allied Powers and Austria, by which the latter renounced at all its rights over Bukovina.

Bibliography:

Florin Constantiniu, O istorie sinceră a poporului român [A sincere history of the Romanian people], Encyclopaedic Universe Publishing House, Bucharest, 2008

Gheorghe Platon (coord), Istoria Românilor [History of Romanians], vol. VIII, tome II, Encyclopaedic Publishing House, 2003.

Marin C. Stănescu, Armata română și Unirea Basarabiei și Bucovinei cu România. 1917-1919 [The Romanian Army and the Union of Bessarabia and Bukovina with Romania. 1917-1919], Ex Ponto Publishing House, 1999.

Mircea Streinul, Ion Aluion [Ion Aluion], Hoffman Publishing House, 2018.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa