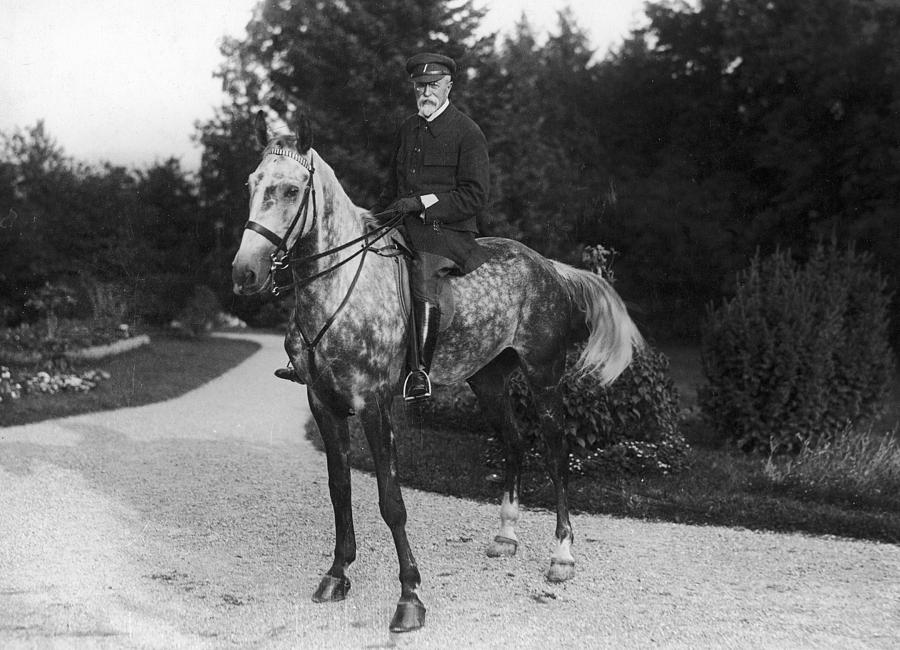

Thomas Masaryk was one of the great personalities of Czechoslovakia’s struggle for independence during the First World War. His initial idea was to reform the internal politics of the Habsburg Empire- transforming the monarchy into a democratic federal state- but gave up and during the first major conflagration supported the abolition of the monarchy. Masaryk, together with other notable figures, joined the Allies, thus contributing to the disintegration of the great Austro-Hungarian Empire. In so doing, Thomas Masaryk remained in history as the “Liberator Father”, being the founder and first president of Czechoslovakia.

Born in a poor family from Moravia, Masaryk took education seriously. He studied in Brno and Vienna, the Austrian capital, and also completed his university studies. In 1876 he took his doctorate in philosophy, with the work Suicide as a mass social phenomenon of modern civilization. In 1882 he became professor of philosophy at the Caroline University in Prague- this at a time when he did not want political entry. “Maybe I was a little nervous and impatient, I came to Prague reluctantly, but nolentem fata trahunt (the Fates lead the willing and drag the unwilling). Later on, everything unfolded on its own, without my will; in all disputes, I stumbled in them without my wanting, but I was wrong by not knowing the conditions” said Masaryk.

First political thoughts

At the end of the nineteenth century, there were already more and more politicians in the empire who supported the autonomy of the Czech lands, but also the transformation of the monarchy into a federation of peoples equal in rights. Masaryk was one of them. In 1891, he was a candidate of the Young Czech Party in the parliamentary elections. He won and entered the Imperial Council in Vienna. An idealist by nature, Masaryk quit his post two years later, as he found it aggravating that party disputes were above the national interest.

In 1900, he founded his own party, the Czech People’s Party, who in the 1907 election won so few votes that in order to receive a mandate it needed to be helped by the Social Democrats. “Later, when I was already in politics, I did not want to set up a new party; circumstances made it so. Even today I do not like to speak in public and I only do it when I have to. Of course, when I am facing a task, I do not hesitate, and what I have begun, I strive to accomplish”.

The struggle in exile

With the outbreak of the Great War, Tomas Masaryk realized that the struggle for the independence of the Czechs and Slovaks can only be achieved from exile. So, along with his daughter, Olga, he left in December 1914, travelling to Rome, Geneva, London, Paris, Russia, United States and Tokyo. He wanted to find allies, to establish ties and to collaborate with the politicians and governments that opposed Austria-Hungary and Germany, to organize from the Czechs and Slovaks from abroad as well as from the ranks of the Austro-Hungarian army, an army of their own to fight alongside the Entente.

Masaryk not only set up the Czechoslovak National Council, but in 1917 he went to Russia to better organize the Czechoslovak military units present there. When Russia surrendered, Masaryk left for America to help relocate the Czechoslovak troops to France. His action was not a hasty one, as he first talked with State Secretary Robert Lansing and then received the support of US President Woodrow Wilson.

He said about politics: “Every policy, both external and internal, is for me a hymn of humanitarianism: I support politics by moral command. I know that this position does not always appeal to politicians, who consider themselves to be very practical and smart; but the experience- and, I hope, not only mine- shows that reasonable and honest policy (Havlíček!) is the most practical, efficient and profitable one. Finally, the so-called idealists, good and honest people, are always right and do more for the state, the people and humanity than the politicians who call themselves realists and rational. The smart guys are, in the end, stupid. They take politics, like the whole life of the individual and society, as sub specie aeternitatis”.

President of the Czechoslovak Republic

On October 14, 1918, Tomas Masaryk was recognised by the Allies chief of the Czechoslovak Provisional Government, and a month later he was elected by the Prague National Assembly as president of the Czechoslovak Republic. He was re-elected as president three times: in 1920, 1927 and 1934- in 1935 he resigned for health reasons. Although the real power was in the hands of the prime minister, only Masaryk through his vision managed to transform Czechoslovakia in one of the most powerful democracies of Central Europe at the time.

Tomas Masaryk, also called “The Grand Old Man of Europe”, died in 1937- a year later the Munich Agreement was signed by which Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Nazis.

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa