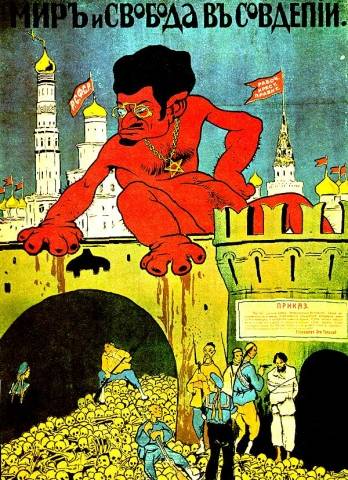

The installation of the Bolsheviks at the helm of Russia in late 1917 would pose a real danger to Eastern European countries, but the virus continued to spread to other European countries. How much of a threat was Bolshevism to the victors of the First World War, especially France and Great Britain?

The first country severely affected was Romania. Following the decision of the Bessarabian Country Council in early 1918 to unite with Romania, the Russian Bolsheviks stepped up their retaliatory measures against Romania. Thus, they arrested Constantin Diamandi, the Romanian ambassador in Petrograd, together with his staff, but even worse was the confiscation of Romania’s Treasure that was kept in Moscow. The Russian Bolsheviks broke off diplomatic ties with Romania. Moreover, Bolshevik troops attacked Romania along the Dniester in 1919. Another threat to Romania was the establishment of Bela Kun’s Bolshevik regime in Hungary. Bela Kun’s troops attacked both Czechoslovakia and Romania. The determined and direct intervention of the Romanian army in the summer of 1919 led to the elimination of Bolshevism in Hungary and the flight of Bela Kun to Moscow.Fortunately, Bolshevik ideas did not have any significant impact on Romanian society. Romania sounded the alarm in Paris about the Bolsheviks, but they were ignored until the summer of 1919 by the leaders of the Great Powers.

The Peace Conference, the Great Powers and Bolshevism

The main political leaders in France, Britain and the United States did not see at the beginning of the Paris Peace Conference (January 1919) the danger that Bolshevism could pose. With one notable exception. Winston Churchill was the only one who foresaw the danger: “The essence of Bolshevism, unlike any other illusory form of political thought, is that it can only be propagated and maintained through violence. […] Of all the forms of tyranny in history, Bolshevik tyranny is the worst, most destructive and degrading”. However, from the summer of 1919 onwards, despite the absence of a direct Bolshevik threat, Britain and France began to pay closer attention, especially since they could not forget the large scale strikes that occurred in the last two years of the war.

Strikes in France

Several serious shutdowns had taken place in the French metallurgical industry in July 1916, and again in May 1918. In the spring of 1917, strikes spread and led to general demands for wage increases and the end of the war. Much more serious were the rebellions in the French army, in May and June 1917, almost half of the French divisions on the Western Front being affected. Even though the rebellions and strikes never turned into a revolution, the memories of 1917 persisted, being amplified by the news coming from Russia with the end of the war. In the spring of 1920, when France was again crippled by a series of strikes supported by the General Confederation of Labour (CGT), the fear of Bolshevik contagion spread to the political and middle classes. The establishment of the French Section of the Workers’ International (soon to be renamed as the French Communist Party) in mid-December 1920 continued to fuel suspicions. Even though Germany remained the main threat to the geopolitical status quo, the new political message of the conservative political class in France was now linked to a double threat coming from the east of the French borders: German revisionism and Russian Bolshevism.

Great Britain, paralyzed by the miners’ strike

For its part, Britain faced multiple labour unrests during the 1920s, including a national miners’ strike in October 1920, which lasted two and a half weeks and brought the country to a standstill. Workers’ unrest culminated in the general strike of 1926, in which workers from all sectors of British industry were involved. However, the causes of the strikes were economic reasons and were not motivated by a desire for a revolutionary overthrow of the existing regime. The Communist Party of Great Britain, founded in 1920, never received significant public support. However, some intellectuals feared that events in Russia and Central Europe might be repeated internally. In London, the social and intellectual reformer Beatrice Webb, co-founder of the London School of Economics with her husband, wrote in her diary on November 11, 1918, the day the hostilities of World War I ceased on the Western Front, the following: “Peace! Everywhere, thrones collapse and the rich tremble in secret. How long will it take for the wave of revolution to catch up with the wave of victory? This is the question that is causing concern at Whitehall and Buckingham Palace and is causing unrest even among the deepest Democrats”.

Bibliography:

Glenn E. Torrey, România în Primul Război Mondial [Romania in the First World War], Meteor Publishing House, Bucharest, 2014.

Robert Gerwarth, Cei învinși. De ce nu s-a putut încheia Primul Război Mondial, 1917-1923 [The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917–1923], Litera Publishing House, Bucharest, 2017

Translated by Laurențiu Dumitru Dologa